As the effects of climate change and patterns of drought propel us into ever shorter, more intense, cycles of water availability, the need to adapt our current water practices and infrastructures become increasingly urgent. In Southern California, much of our water infrastructure is passing the century mark, while population growth creates more strain on these systems. In the past several years, my teams at RIOS have been working on two projects that represent both the optimism of the California landscape and the precarity on which that optimism was built. Our work addresses the inevitable risks of dated infrastructure while acknowledging deep histories and evolving desires for water to offer respite in an arid landscape.

Descanso Gardens Master Plan

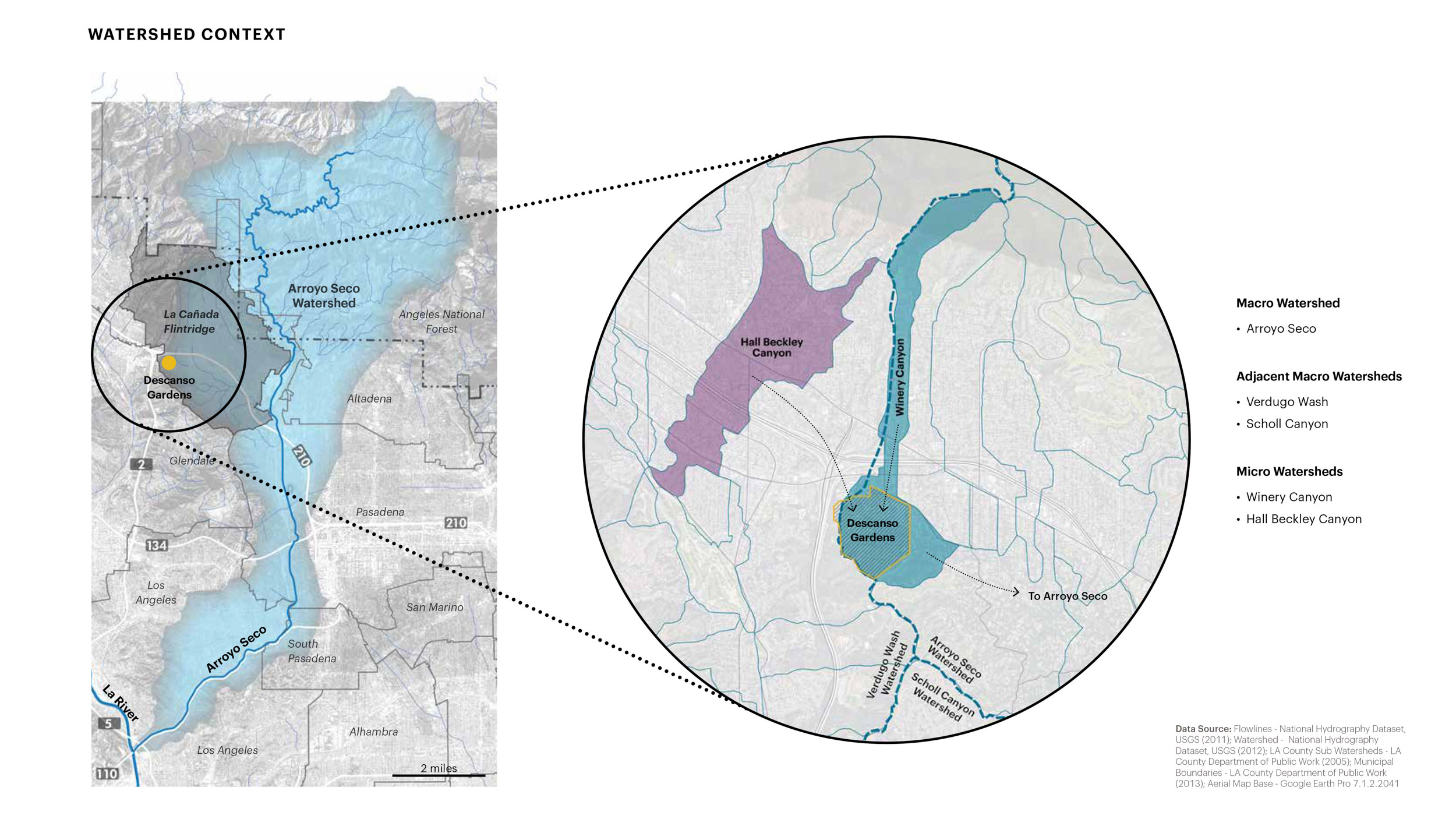

The first project is our master plan for Descanso Gardens, a 160-acre public botanical garden located in the La Cañada Flintridge. The gardens are situated in the foothills above Los Angeles in a valley between the outcrop of the San Rafael Hills and the wildlands of the Angeles National Forest. Numerous channelized tributaries that drain into the Arroyo Seco cross this terrain. Descanso has its own channel that bisects the garden, the Winery Creek Channel. The gardens opened to the public in 1950 on the established estate of Manchester Boddy.

Boddy was a bit of a water prospector in the early days of La Cañada. To support his estate and budding horticultural interests, he purchased 440 acres in the adjacent canyon of Hall Beckley, including a spring-fed stream several miles and elevational feet above the estate. Captured water from this spring was piped across what would become suburban neighborhoods, commercial districts, and a sunken 210 freeway. It is still a wild and outrageous feat today, let alone in the 1940s. The garden depended on this water source for decades to irrigate the gardens and activate its water features. This mid-century engineering has proven its value, but was plagued by breaks, disruptions, and maintenance challenges that created great vulnerability for Descanso’s many botanical collections.

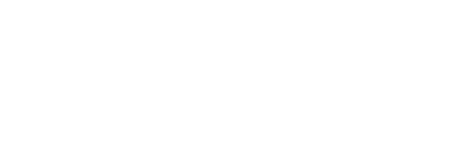

Descanso Gardens Water Infrastructure Plan

La Casa de Maria

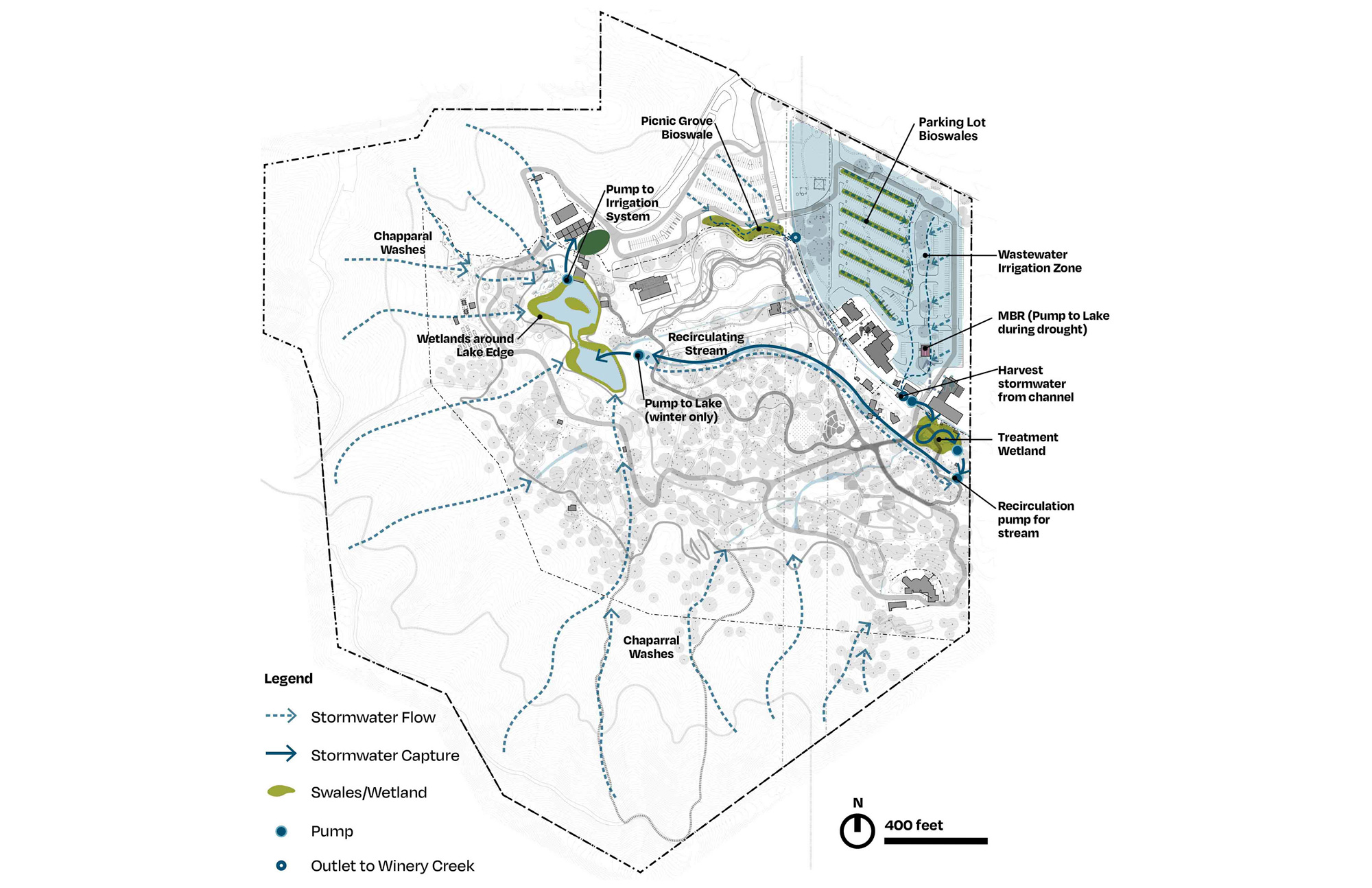

The second project situated on a 24+ acre native oak woodland and riparian corridor along the San Ysidro Creek in Montecito, California, is La Casa de Maria. The site lies on a sloping incline between the Santa Ynez Mountains and the sea. The site was developed in the 1920s with extensive citrus orchards and gardens that were irrigated with water that flowed through San Ysidro Creek. In the 20th century, the property was transformed into a novitiate and spiritual retreat for the Immaculate Heart Community of Los Angeles. The property was devastated by the 2018 mudslides and floods following the Thomas Fire, which destroyed buildings, scoured the land, and left piles of sediment and rock in a reformed terrain.

While the master plan work for these projects is extensive, the opportunity to reformulate the water story is foundational to framing the future for both institutions. Each dependent on a fragile reliance on aging infrastructures and early to mid-century engineering which needed reconsideration. It was imperative that our planning address the inevitable risk that these infrastructures faced.

Gathering the Watershed

Framing these bounded sites’ water challenges within the greater topographies that drained onto them was essential to both projects. La Casa de Maria came to terms with its position in the watershed after the mudflows of 2018, which tragically demonstrated the implications and risks involved in a living and dynamic watershed. The historical aerials revealed the morphology of scour marks that indicated past events, where the San Ysidro Creek broke its banks and modified the landscape.

1920

1960

2016

2018

La Casa de Maria aerial view over time

At Descanso, the channeled and impounded waters diminished the availability of site water as it bypassed instead of permeating the site. In the lake this containment exacerbated the sedimentation at the low points without a system that flowed and naturally drained with rainfall cycles.

The broader basin topography presented both resources and lessons for the redevelopment of water within these sites. It also suggested how a new generation of infrastructure could be both better calibrated to nature and ultimately more resilient for the future.

Descanso Gardens Watershed

Layering Old and New

The approach to integrating new water projects into these landscapes was to acknowledge and synthesize the previous histories both natural and man-made. Beyond acknowledging the existing topography, the existing structures and modifications to the land—irrigation ponds, man-made streams, natural arroyos, and bridges—were treated as the framework for adding, altering, and integrating more systematic and performative hydrology to the sites. The original drainage features were built out of necessity and ingenuity by the original occupants, and often in an ad-hoc manner. They did not delve into a site analysis before creating these features, they were improvisational and therefore not optimized for future resilience or a transformed climate.

A new hybridized set of solutions that combined hard engineering with soft ecological systems and modifications to hydrological patterns would be necessary. Hard engineering systems in the forms of pipes, cisterns, pumps, and valves would be combined with landscape solutions in arroyos, water gardens, and wetlands to clean, collect, infiltrate, and convey water across the sites. There’s nothing new about these multi-beneficial landscape techniques, but it gave new purpose to areas where the site’s potential had laid latent for decades.

After the debris flows of 2018, the San Ysidro Creek was deepened by the event and the possibility for endangered steelhead trout to venture further upstream and gain new habitat was enhanced by more consistent flows in the creek. Therefore, it was essential for La Casa to take on an initial project to de-couple its agricultural irrigation from its century-old reliance on the flows from San Ysidro Creek.

San Ysidro

The restoration of a dry arroyo in the middle of the site will create a renewed conveyance to collect the majority of the stormwater for re-use at the lowest point of the site, into a cistern for later use. Over time, this storage will be layered with additional rainwater, greywater, and potentially blackwater harvesting techniques which involve gradients of treatment, storage, and re-use.

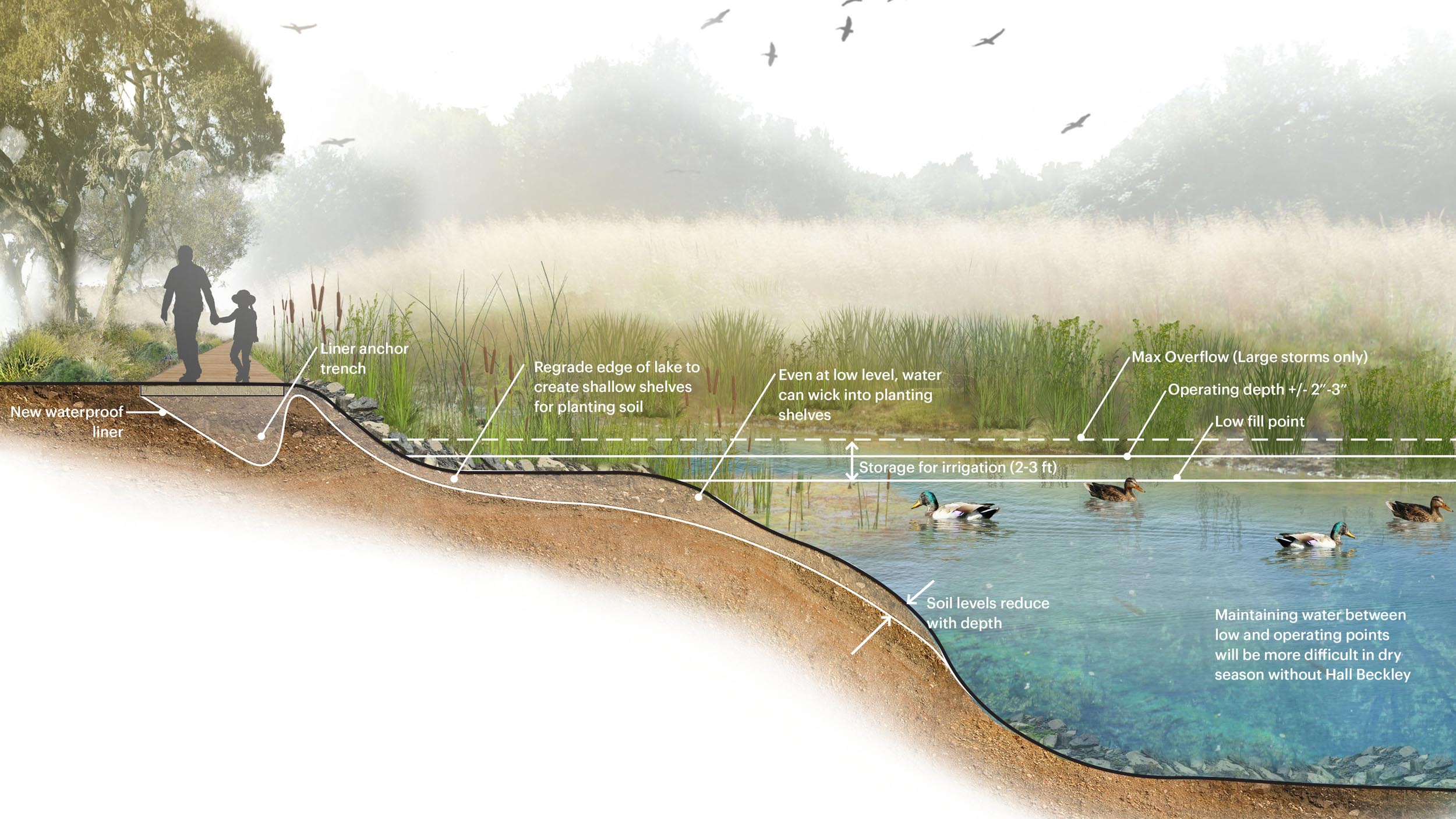

For Descanso, where once there was a clay-lined pond, there will now be a new dynamic floating wetland edge, for biofiltration and habitat. On the other side of the site, water will be harnessed and diverted from the Winery Creek Channel. Disrupting the current regime which rapidly transports water away from the site and out to sea.

Section view of the lake at Descanso Gardens

This will allow for the collection of an untapped water source to feed the gardens with irrigation that will ultimately infiltrate into the ground. The other element aiding in the water balance is a new blackwater treatment system, this will eliminate Descanso’s reliance on septic storage and be phased in overtime, to create a new source of water that is at the forefront of water harvesting.

All these techniques activate the site with water in new ways that enrich the landscape with seasonal shifts and renewed habitat, where wildlife will thrive more fully and enrich the natural experience. While there is engineering at the heart of many of these systems the layering of performative landscapes will shift the experience and ecology of the site over time.

Climate + Self Sufficiency

Capturing and finding new sources for on-site water to create self-sufficient sites is necessary at the start of this century. While we can’t entirely predict the water availability in any single rain year we know that we need to plan for scarcity and more intense rain events and buffer sites with reservoirs and adaptable landscapes to absorb and capture water when it comes.

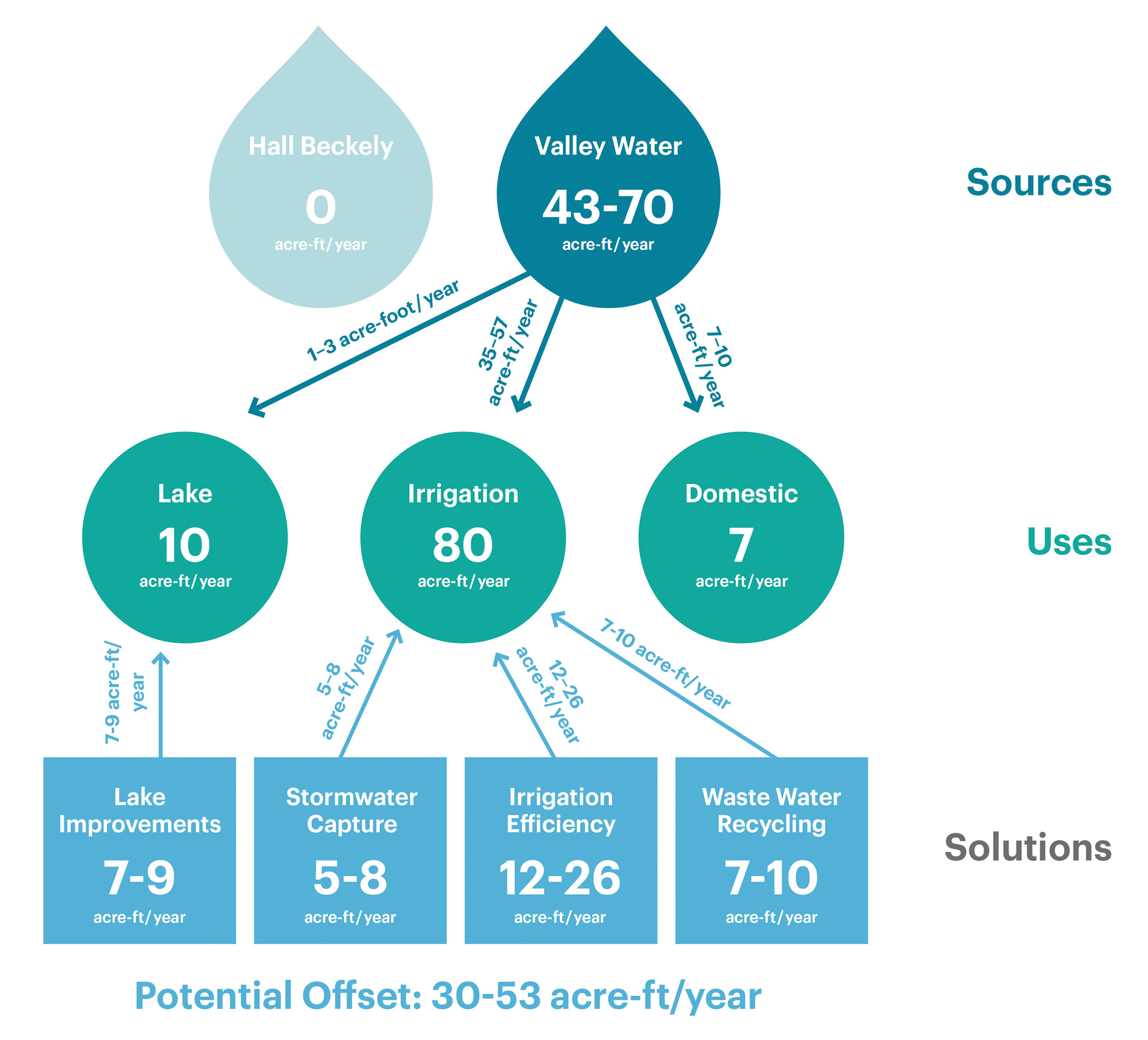

Ultimately these two projects will begin to offset tremendous amounts of water that were diverted from natural waterways or withdrawn from municipal sources. At Descanso, we planned to offset 33-66% of the water used for irrigation and domestic uses depending on the rain year and to create full independence from nearby mountain canyon resources.

Descanso Gardens proposed water metrics

At La Casa, as an initial offset, we looked to capture and store 150,000 gallons of rainfall per year for re-use in the heritage organic orchards. Ultimately by layering in another rainwater harvesting, we plan to achieve zero potable water for irrigation. These projects are victories for water conservation and habitat creation. They are also wins for these organizations, with numerous sources of funding that are available to aid in implementation. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has numerous Watershed Restoration, Planning and Protection grants. One which will help La Casa’s initial project. Also, the County of Los Angeles grants funds through their ‘Safe and Clean Water’ program, enacted after the passing of Measure W in 2018. This amounts to several millions of dollars in infrastructure work for these sites that can be publicly funded.

Water as a natural occurrence and an introduced element will continue to exist at these sites, and the need to irrigate or be present with water features has not been eliminated. Yet it has been considered with the need for balance, anticipated fluctuations, and systems that will evolve over time. While the risk of running dry or being without water has been reduced, the benefits to the sites are exponential – enhancing habitat, visitor experience, and our natural connections.