The word pattern is defined as “a repeated decorative design” based on its common application to a surface. However it is the alternate definition of this term, “giving a regular or intelligible form to [something],” that is more interesting because of its potential for placemaking.

As the fabric of our City evolves over time, significant architecture, plazas, and landscapes remain landmarks of public memory. Two recently completed projects, The Music Center Plaza and Christ Cathedral Plaza, are significant cultural works and public spaces that represent the significance of urban pattern in placemaking. With their renovation, they are remaking beloved places as pedestrian-centered experiences and shifting the expectations of the city that surrounds them.

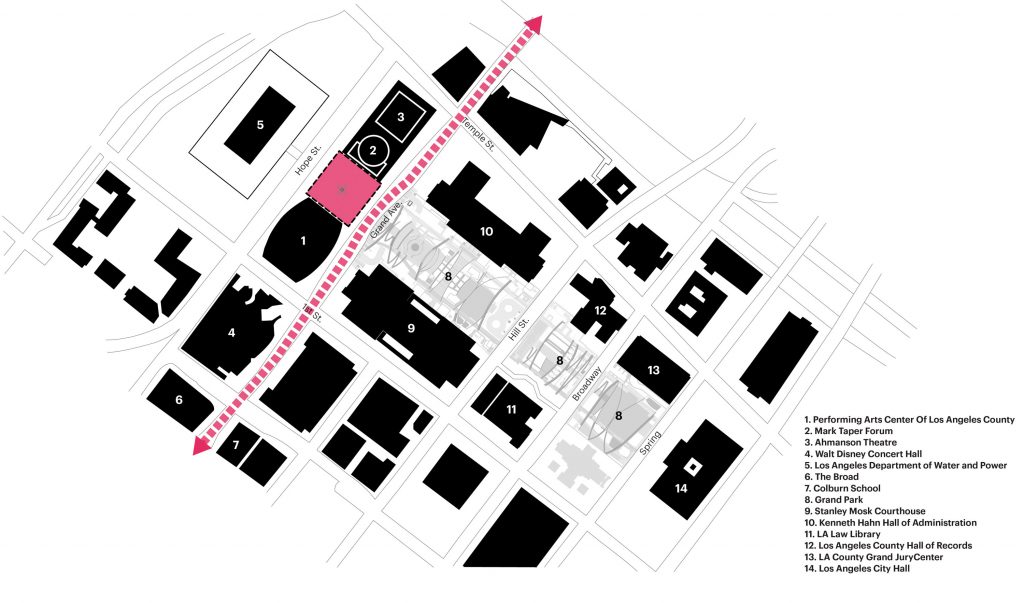

Case Study: The Music Center Plaza

An Elevated Campus

The aspiration for the renovation of The Music Center Plaza was to transform the central circulation area into a true outdoor performance venue, capable of supporting a variety of new art forms not yet dreamed of.

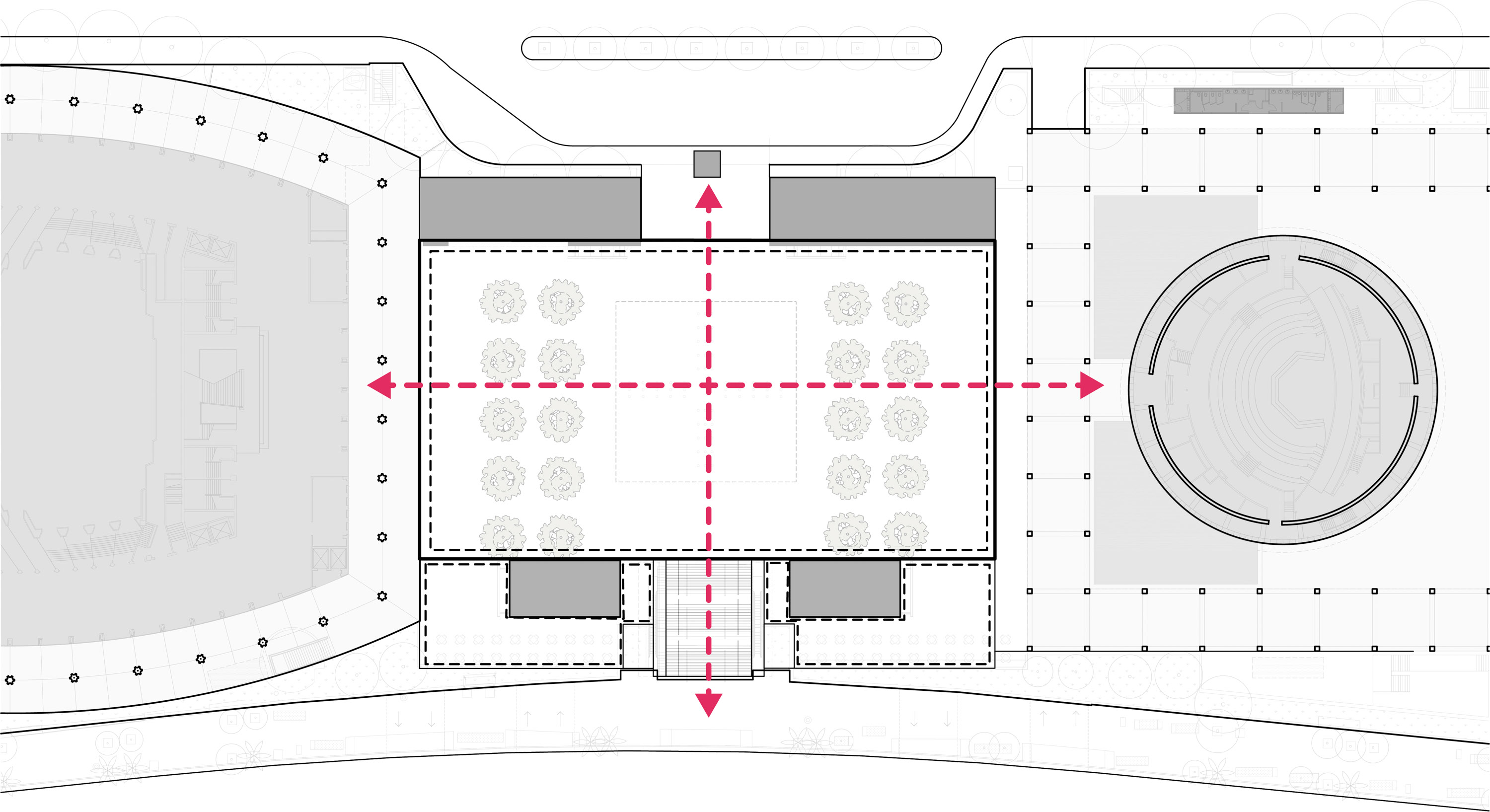

Two design moves allow for this metamorphosis: first, leveling out the sunken portion of the existing Plaza to extend a continuous accessible paving surface to maximize flexibility in staging events while creating a plenum where a network of media hydrants are recessed, and second, relocating the Peace On Earth Sculpture from the center of the Plaza to the Hope Street entrance to maximize sightlines throughout the Plaza. This yielded a 35,000-sq.-ft. outdoor performance space, the 5th venue at The Music Center, primed to support a wide variety of cutting-edge performances.

The strategies used to create a performance venue also provide an amazing opportunity for a true public space that can welcome an increasingly diverse community of Angelenos. Where the original sunken plaza once forced visitors to traverse through an aggregation of small spaces captured in between tree wells, the fountain, and the sculptures, the new raised Plaza provides a continuous expansive space that allows for larger community gatherings – for Angelenos to come together in a shared cultural or community experience.

Inherent Symmetry

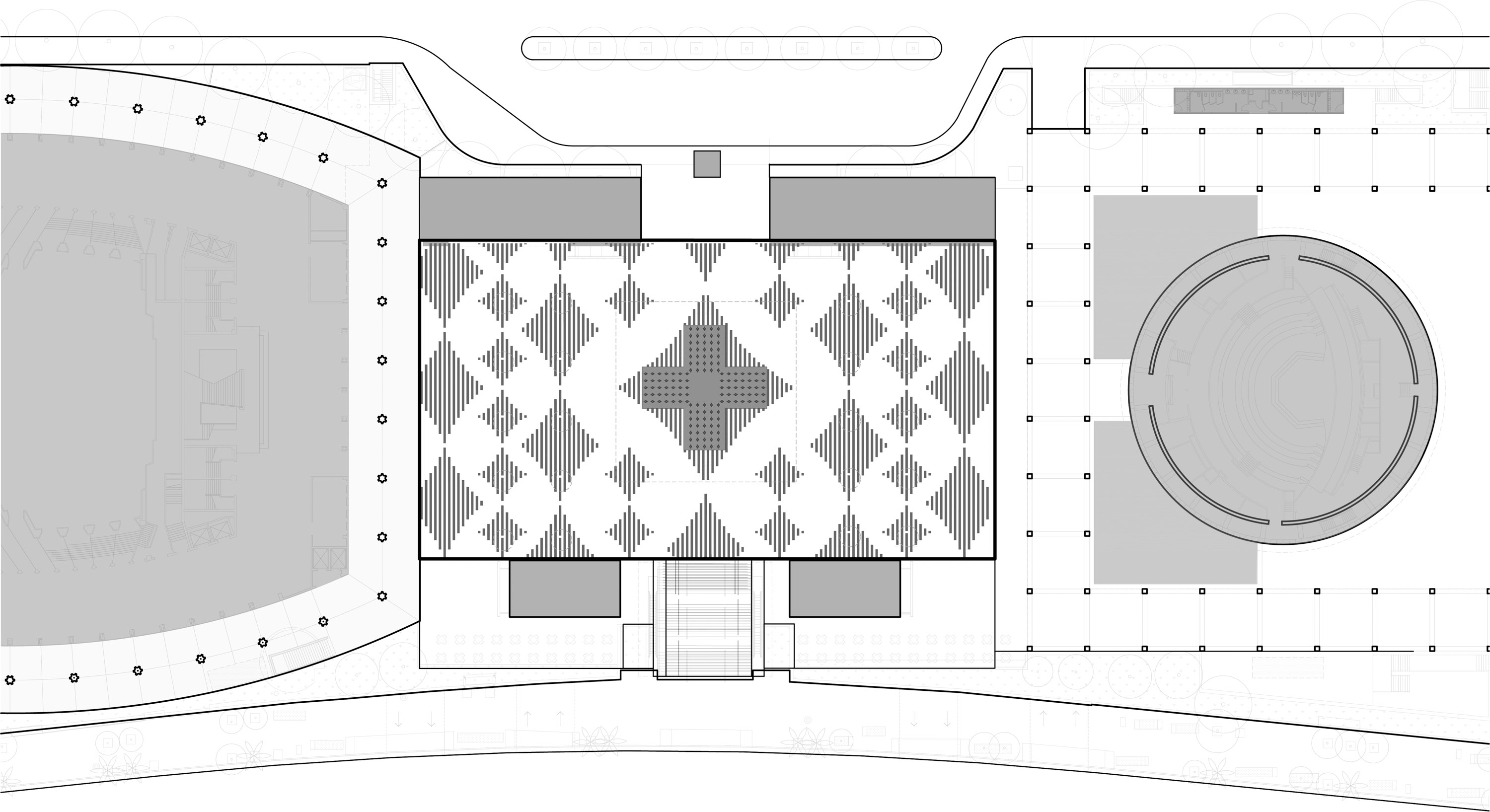

A new paving “carpet” inscribes and unifies this new zone of public gathering and artistic programming. The pattern was carefully considered and explored various narratives inspired by The Music Center – including elements of sound, scores, frequency, movement, dance, celebration, and the historic patterning and materials found in the interior design elements by Tony Duquette and Welton Beckett.

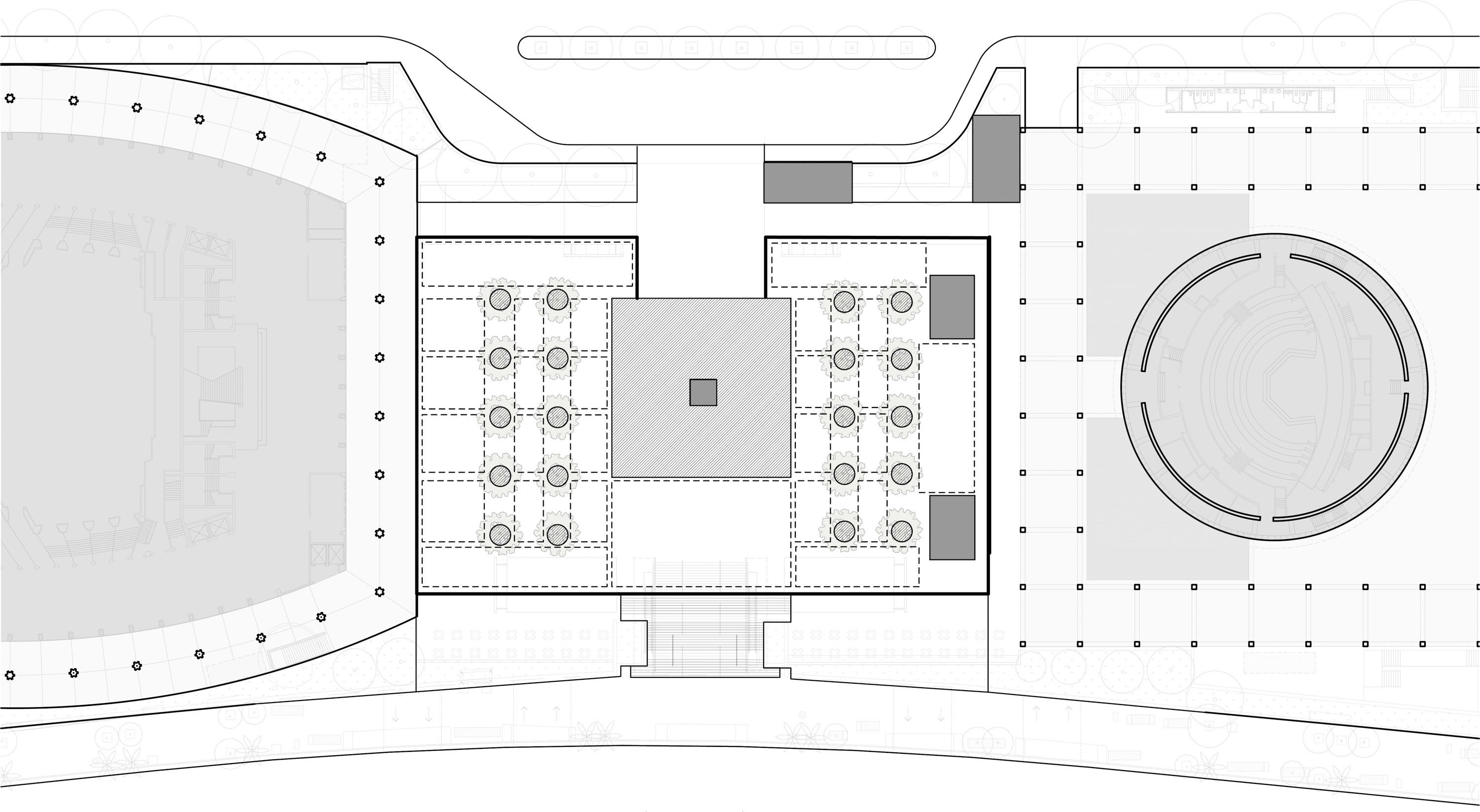

A variety of technical issues were also considered. Due to operational requirements, the new Plaza had to be traversable by forklifts and other staging equipment. This required a standard 12” x 12” concrete paver appropriate to vehicular traffic, except for over the historic fountain, where it was necessary to maintain a 36” x 36” paver dimension coordinated with the existing fountain jet and light layout.

The classically symmetrical architecture of The Music Center campus generates the impression that the Plaza elements are tied in to an inherent symmetry. However, at the Plaza scale the paving pattern in fact had to negotiate slightly asymmetrical conditions – the column grid of The Mark Taper Forum does not match the column grid of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and the existing tree well layouts are not symmetrical around the east-west axis of the Plaza. In addition, the varied sub-surface conditions and elevations also needed to be mitigated to seamlessly unify the new public Plaza. The budget dictated additional parameters: a maximum of 2-3 different colors, no custom cuts, and no ornamental tree grates at the tree wells.

An extensive study of almost 50 distinct patterns – exploring themes of dance, movement, performance, and celebration – led to the selection of a diamond pattern inspired by the existing mirror starbursts surrounding the stems of the iconic chandeliers in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. This pattern met the technical criteria, was legible, and conveyed a language of adornment inspired by Tony Duquette that is appropriate to the history of the site.

The varying scales of this reinterpreted diamond motif erases the fragmented pedestrian pockets that previously existed between the tree wells, and stretches the modular paver system across the surface to create a public Plaza that encourages the surrounding community to gather, linger, and share a cultural experience.

Case Study: The Crystal Cathedral

The Sacred Heart of the Campus

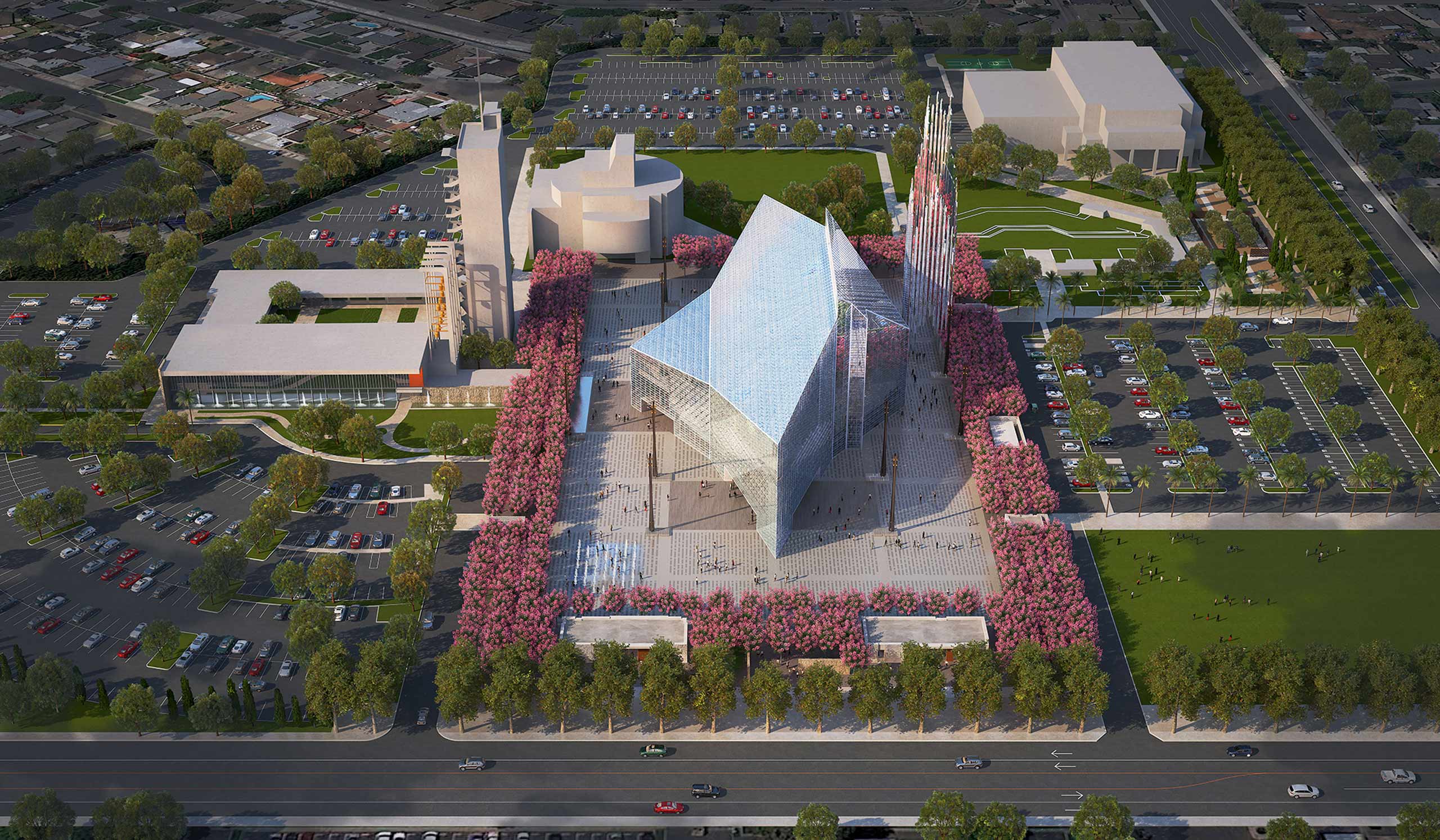

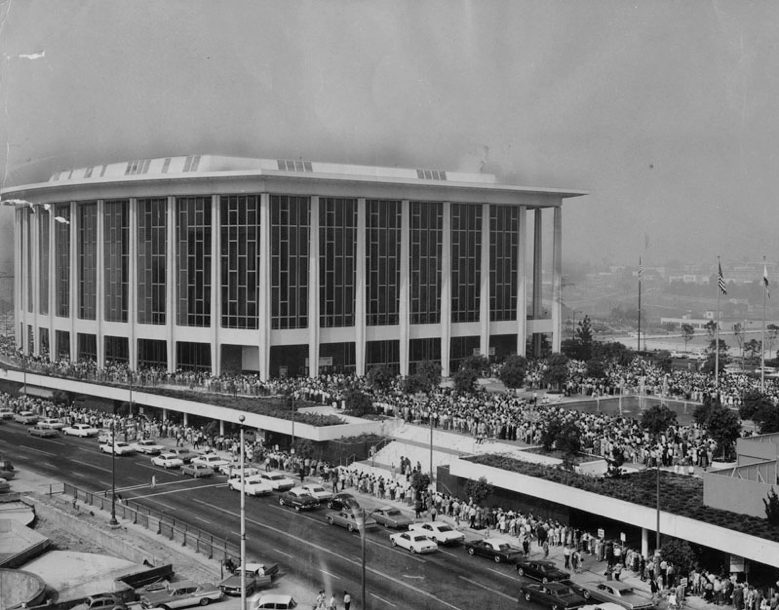

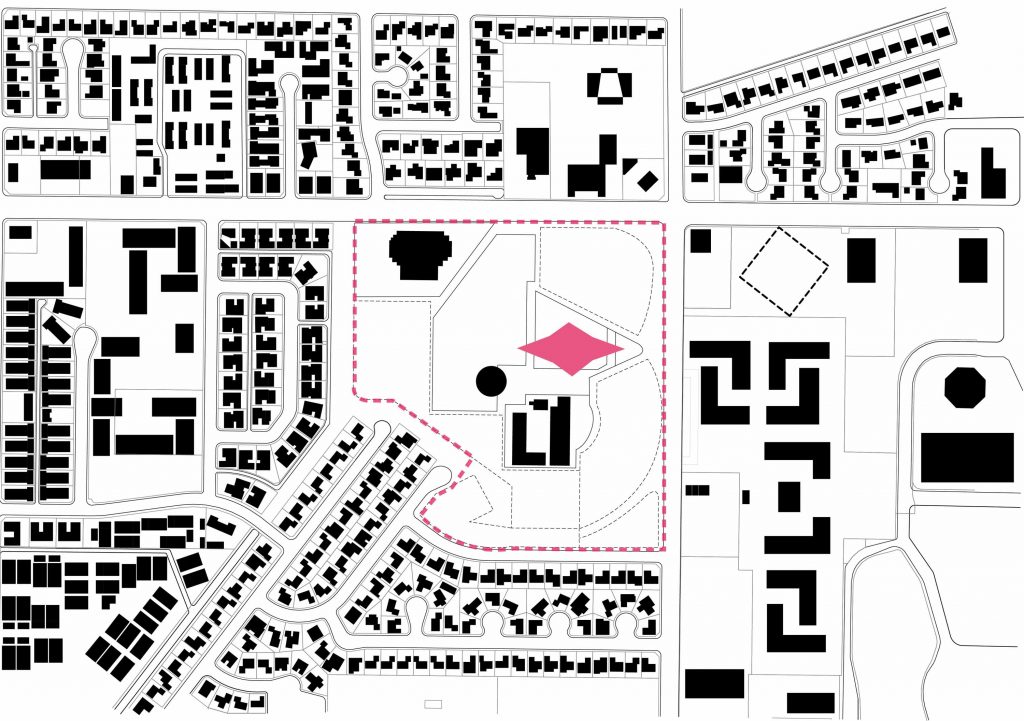

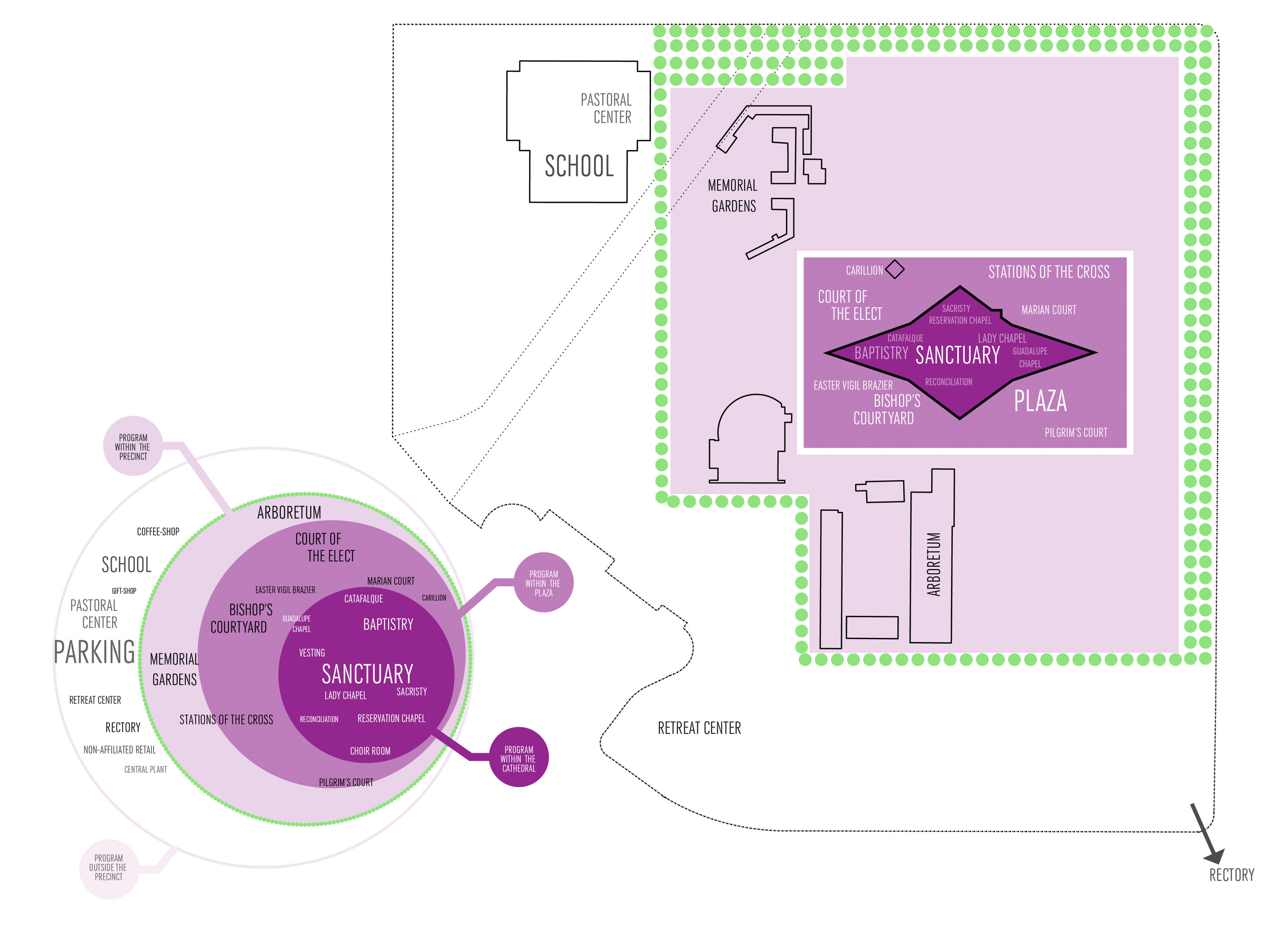

Christ Cathedral, along with its campus, is a dream of Modernism and is one of the experiments of post-war car-centric urban planning theories, the by-product of which was this drive-in church.

Scale is a thing that is difficult to define in Orange County. Acres of hard surfaces, either concrete or asphalt, have created opaque patches that prevent people from permeating urban mega-blocks. The existing open space around Christ Cathedral shared the same deficiency prior to the renovation.

Since this unprecedented drive-in liturgical public space was realized in the 1960s, the site and relationship to this iconic landmark has not been reevaluated to address a functionality more appropriate to our current culture and changing views on the primacy of the car. The peculiar mixture of parking lot, immense lawn, and concrete slabs created a disjointed relationship between the neighborhood, California’s outdoor tradition, and this iconic religious building.

The drive-in church (Arboretum) before the construction of Crystal Cathedral. Photo by RIOS.

Our Vision

In considering what this plaza should be, our approach was twofold: reduce the scale and reinforce connection to the iconic landmark. The pattern design is the key to hold the Cathedral and the plaza together. Our scheme, which won a design competition in 2014, upholds that decoration is not the right approach for the campus. Instead, the Cathedral should be placed in the sacred heart of a new plaza, a place that encourages procession as one approaches the renovated structure at its center.

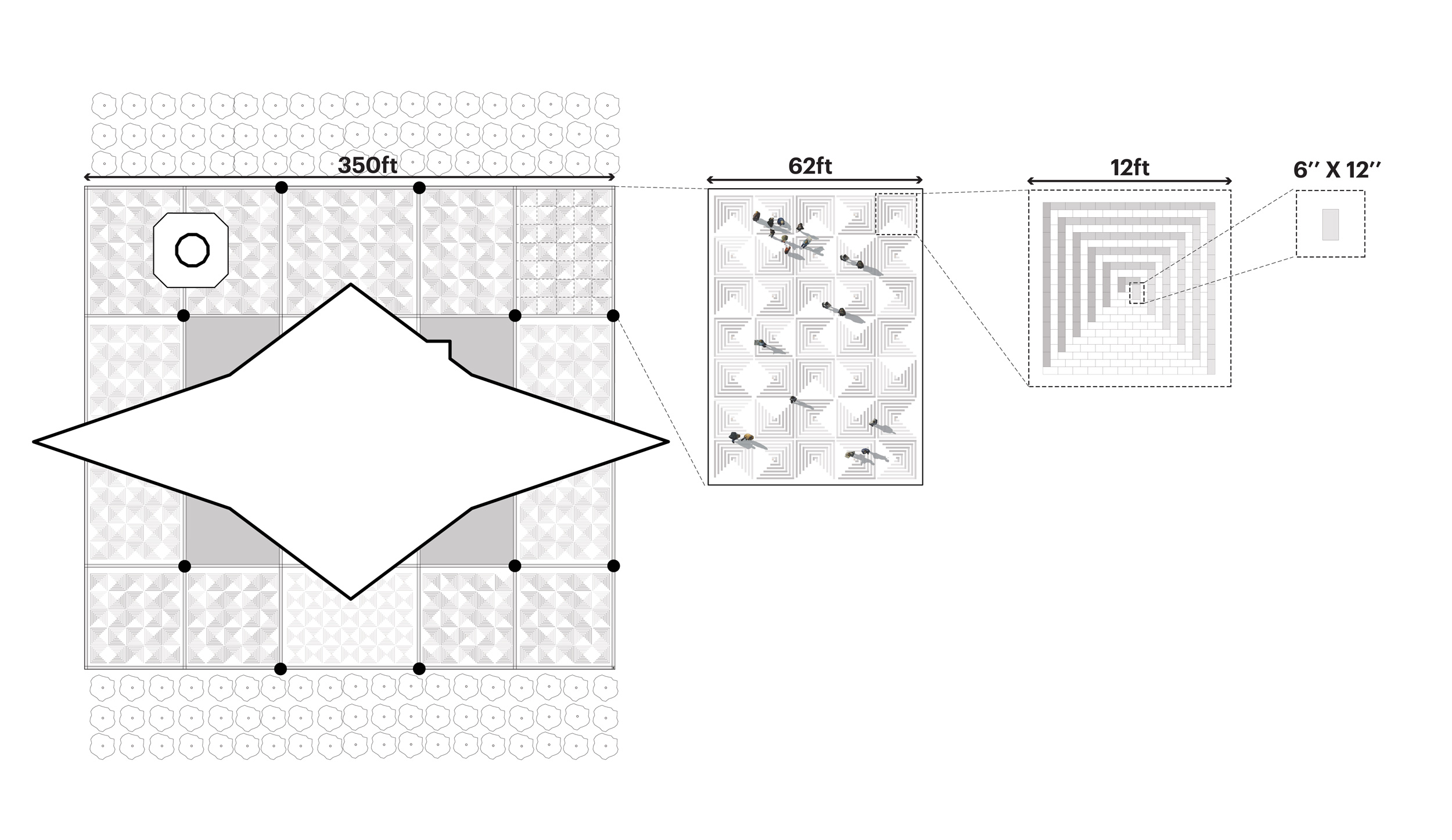

The holistic picture of the design is based on the foundational element of the smallest unit — 6”x12” concrete paver units donated to the Diocese to cover the surface of the plaza.

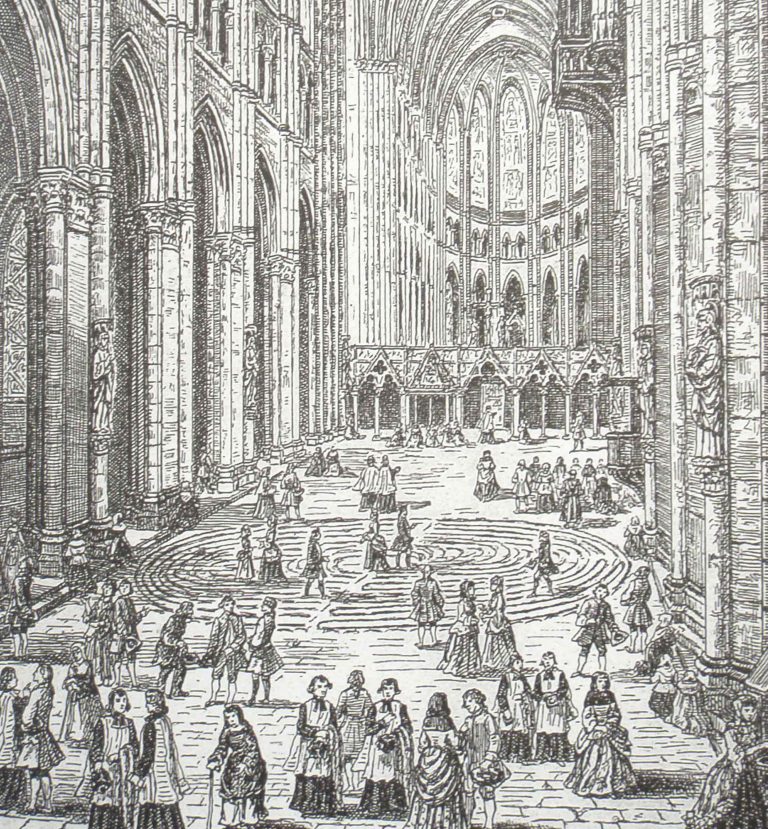

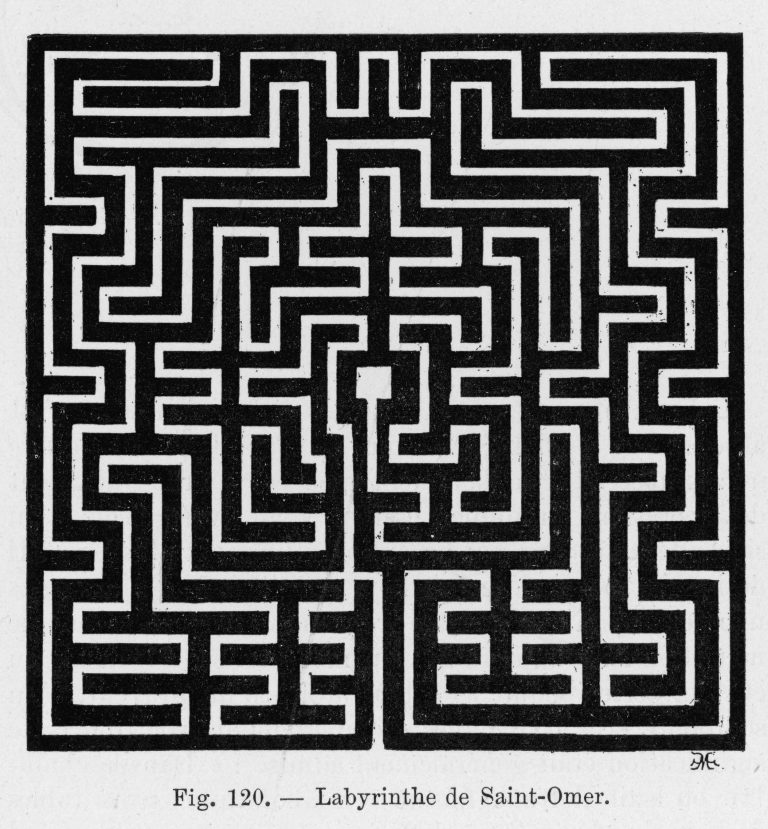

A quatrefoil labyrinth, common in European churches, inspired the pattern. The idea of the labyrinth was originally described by the phrase “chemin de Jerusalem,” or path to Jerusalem, a path of procession that quiets the mind in prayer and reflection. Its symmetrical beauty possesses subtle variations in each of the four quadrants.

Left: Chartres Cathedral, about 1750, Jean Baptiste Rigaud. Right: The St. Omer labyrinth, The Abbey Church St. Bertin in Saint-Omer (France), 14th Century.

A Meaningful and Tangible Plaza

The design team started with six options and landed on one arranged in a rotating square configuration to resonate with the quatrefoil shading inside the Cathedral. Pavers with graduating shades of grey are arranged within the quatrefoil module to represent shading of sunlight at different angles. Ten modules of labyrinth pattern were further assembled into sections or “pages” that define the plaza at a 12-foot scale.

Unlike The Music Center, the Cathedral’s plaza is comprised of 14 pages. Each has a Carrara marble block representing one station of the 14 Stations of the Cross, establishing a progression and sequence. Many historic church plazas uses high-contrast patterns to delineate gathering areas. We designed the surrounding plaza to create a supporting framework for a wider range of liturgical and non-liturgical events and programming which create and nurture community bonds.

Left: Interior Photo of Christ Catholic Cathedral Renovation. Right: Labyrinth Pattern Design

Unlike The Music Center, the Cathedral’s plaza is comprised of 14 pages. Each has a Carrara marble block representing one station of the 14 Stations of the Cross, establishing a progression and sequence. Many historic church plazas uses high-contrast patterns to delineate gathering areas. We designed the surrounding plaza to create a supporting framework for a wider range of liturgical and non-liturgical events and programming which create and nurture community bonds.

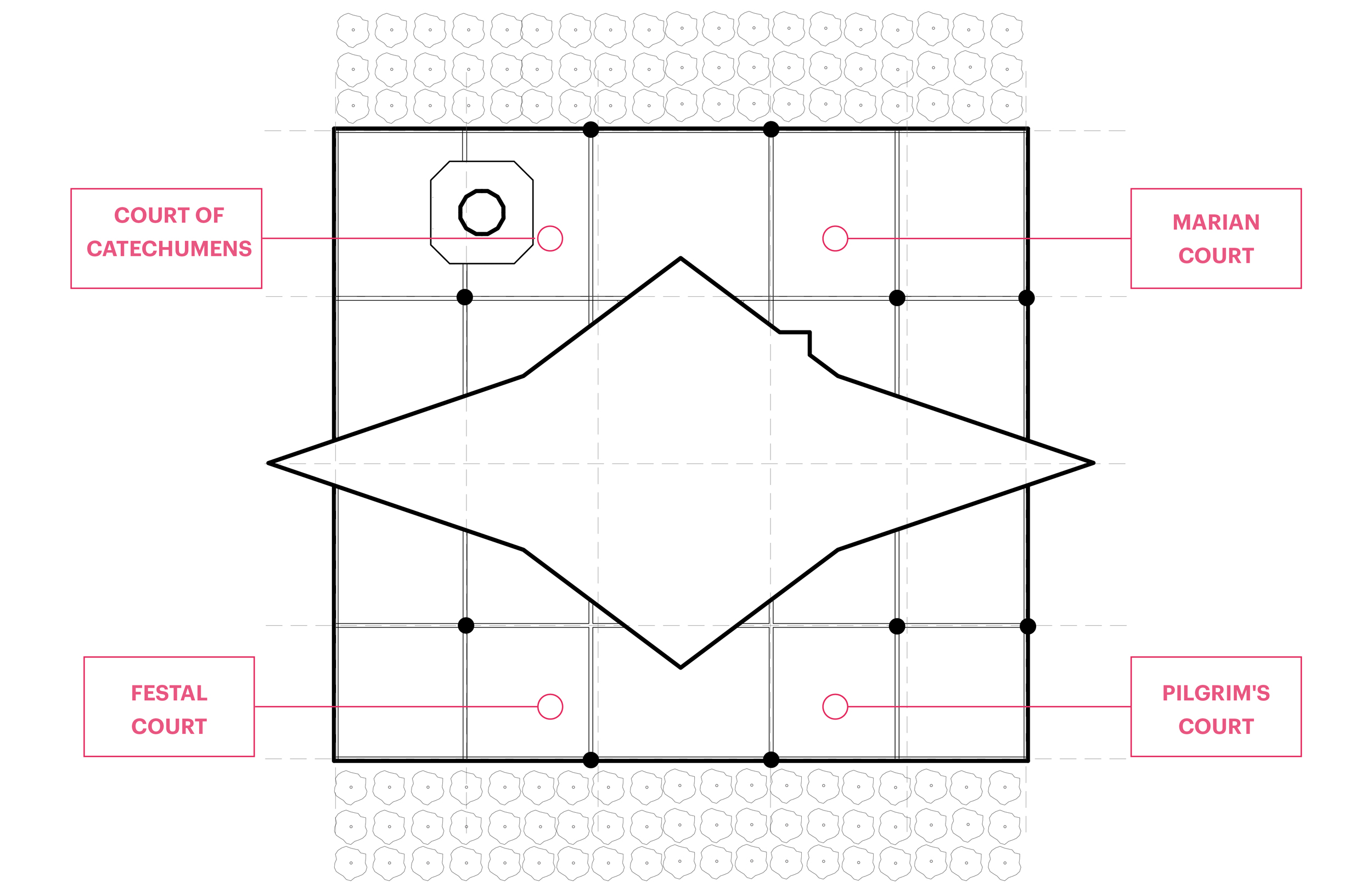

The 350-foot-wide plaza is zoned into four courts: The Pilgrim’s Court, the Festal Court, The Marian Court, and the Court of the Catechumens. The courts share a scale of between 65 and 80 feet in width and can accommodate around 1,500 people. Though the idea of elevating procession is essential for the sacred plaza, it was also critical that it embrace the cadence and events of everyday life.

The current border of the plaza is an edge that contains a mix of shrines, chapels, visitor services, and support elements for the Cathedral — a modern interpretation of the traditional ambulatory of the Cathedral where sacred elements are traditionally housed and where various faith communities can leave their imprint. This frame is a liminal space where visitors making the transition from the profane world into the sacred, holy space of the Cathedral.

In a future phase, this border will be planted as a shaded, tree-lined threshold. Flowering trees were chosen to provide color and unique character throughout the year, connecting to the four seasons and cycle of Catholic life.

Urban Transition

While these two case studies respond differently to the transition from mid-Century car culture to human-scale engagement, each uses pattern as a strategy. The Music Center Plaza’s urban-scaled paving “carpet” unifies a newly demarcated public space with gathering and outdoor performance as the focal point. In contrast, Christ Cathedral’s paving frame utilizes pattern to help worshipers transition to the sacred space at its center. Their common thread is that each design tells a story, informed by history and precedent, to create an experience that is very much about the future.

Below: Christ Cathedral Rendering by RIOS.