Southern California’s weather cycle of fire, floods, and mudslides highlights the limitations of static infrastructure designed to control natural processes. A few years ago, RIOS saw this shortcoming as an opportunity to re-think the relationship with this extreme environment, and to re-imagine the role landscape architecture can have in shaping it.

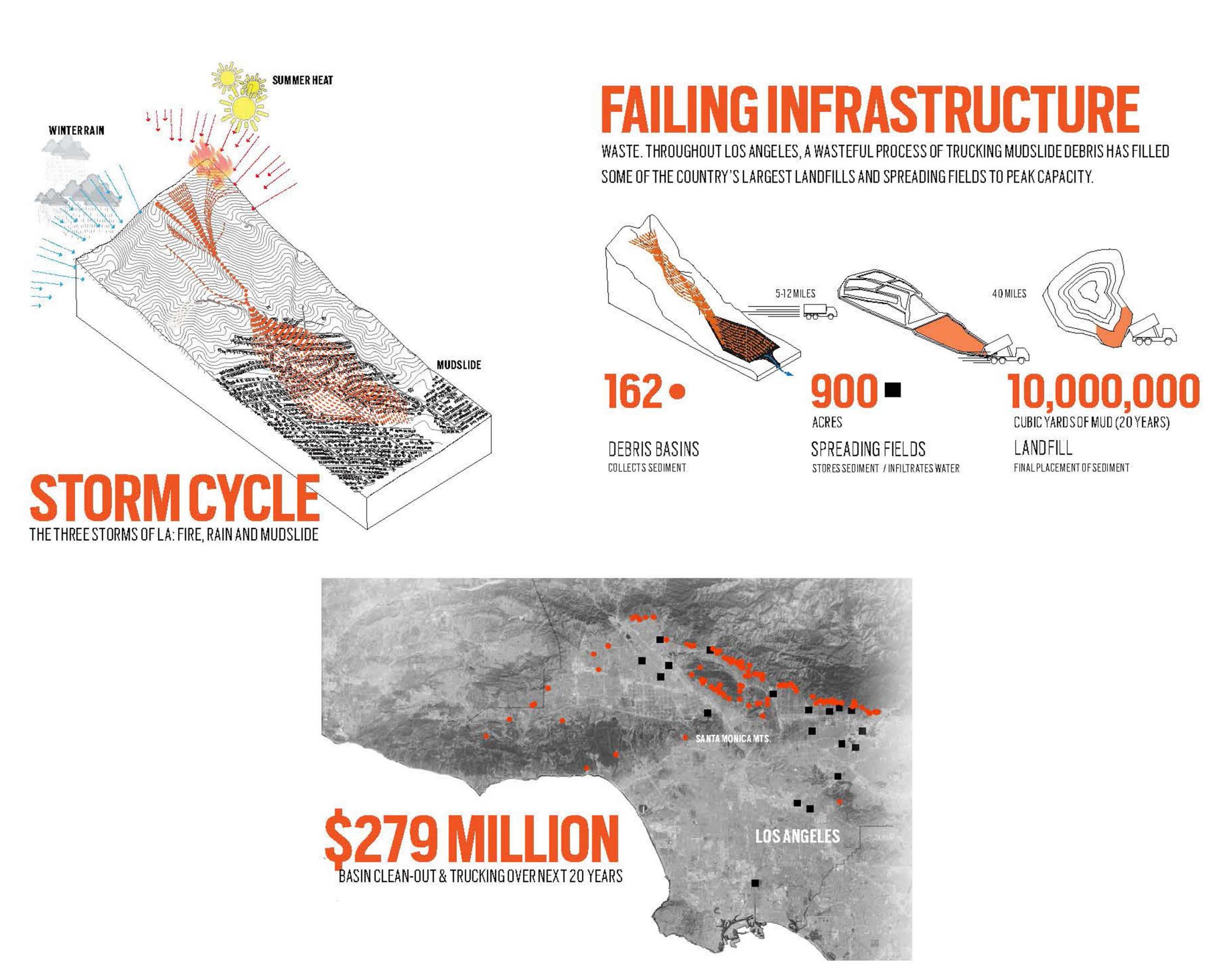

Fire. Flood. Mudslides. These three components of L.A.’s extreme weather cycle create a deadly combination. Fire clears vegetation from Southern California’s steep canyons, leaving them vulnerable to flash floods and perilous mudslides. For most of the 20th century, City, State, and Federal agencies have attempted to control these natural processes as communities sprawled deeper and deeper into once-uninhabitable canyons. But as this infrastructure, designed to restrain nature, comes to the end of its 50-year lifespan, we wondered how to fundamentally rethink the way we approach prevention?

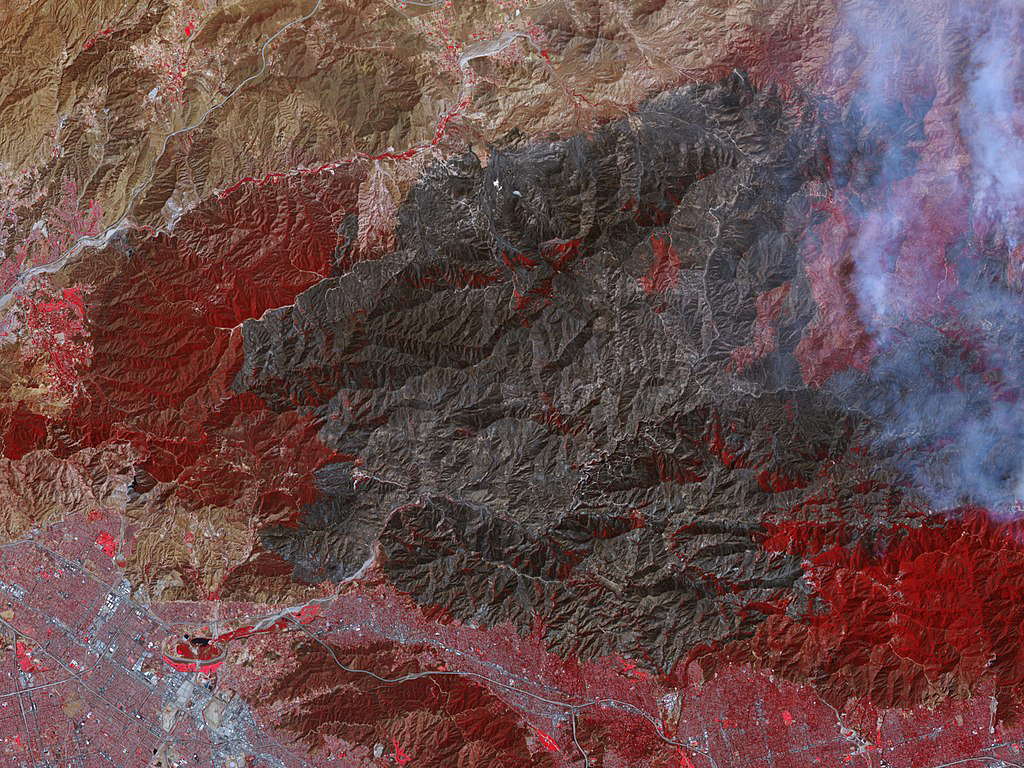

An aerial view of the 2009 Station Fire, which ravaged a 252-square-mile area of Southern California’s La Crescenta foothills, and sparked multiple catastrophic mud slides was the result of severe climatic conditions, cyclical weather cycles, and an outdated, aging infrastructure.

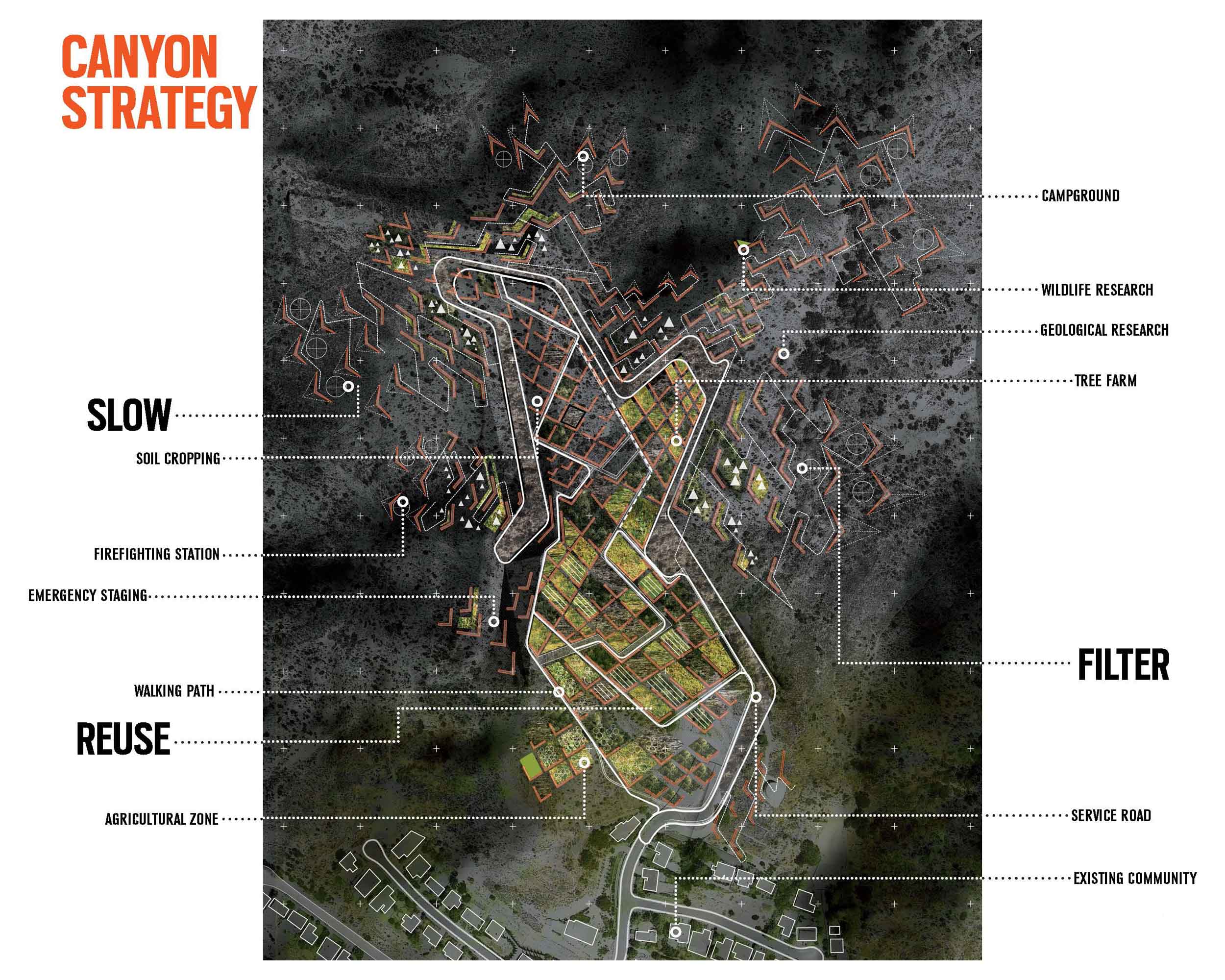

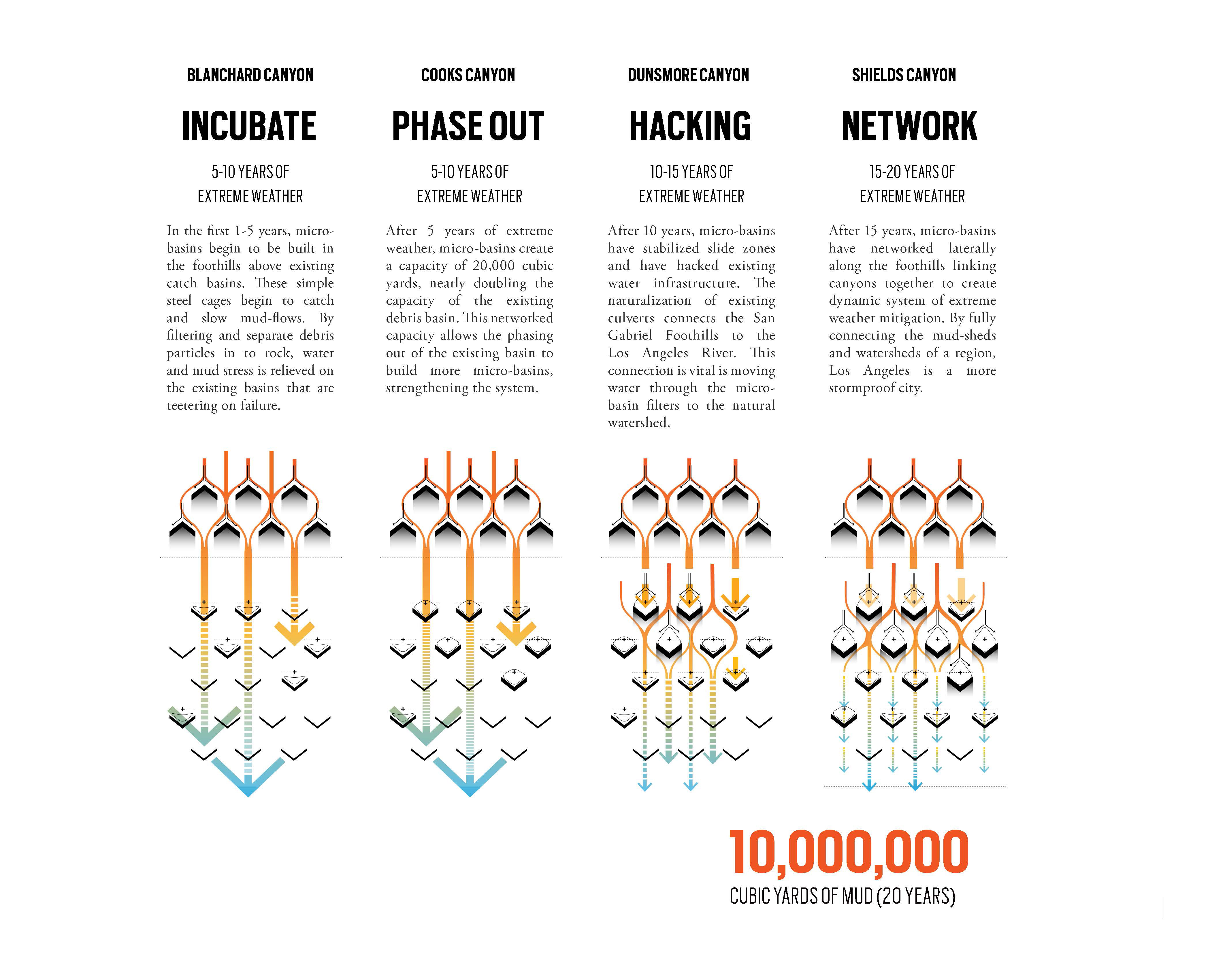

SLIDE deconstructed the systems that failed during the 2009 Station Fire in the Angeles National Forest to envision a more resilient infrastructure for California communities prone to the cyclical hazards of fire, flood, and mudslides. By hacking into the natural processes of mudslides and wildfire, our strategy utilizes the material produced by the fire and mudslides as a safeguard against future disasters.

“Landslides and other ‘ground failures’ cost more lives and money each year than all other disasters combined, and their incidence appears to be rising. Nevertheless, the government devotes few resources to their study – and the foolhardy continue to build and live in places likely to be consumed one day by avalanches of mud.”

— BRENDA BELL, THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY (JAN. 1999)

The research focused on three areas: examining the storm cycles of fire, rain, and mud slides; dismantling the failures of existing infrastructure; and projecting the financial costs of the current system.

The research focused on three areas: examining the storm cycles of fire, rain, and mud slides; dismantling the failures of existing infrastructure; and projecting the financial costs of the current system.

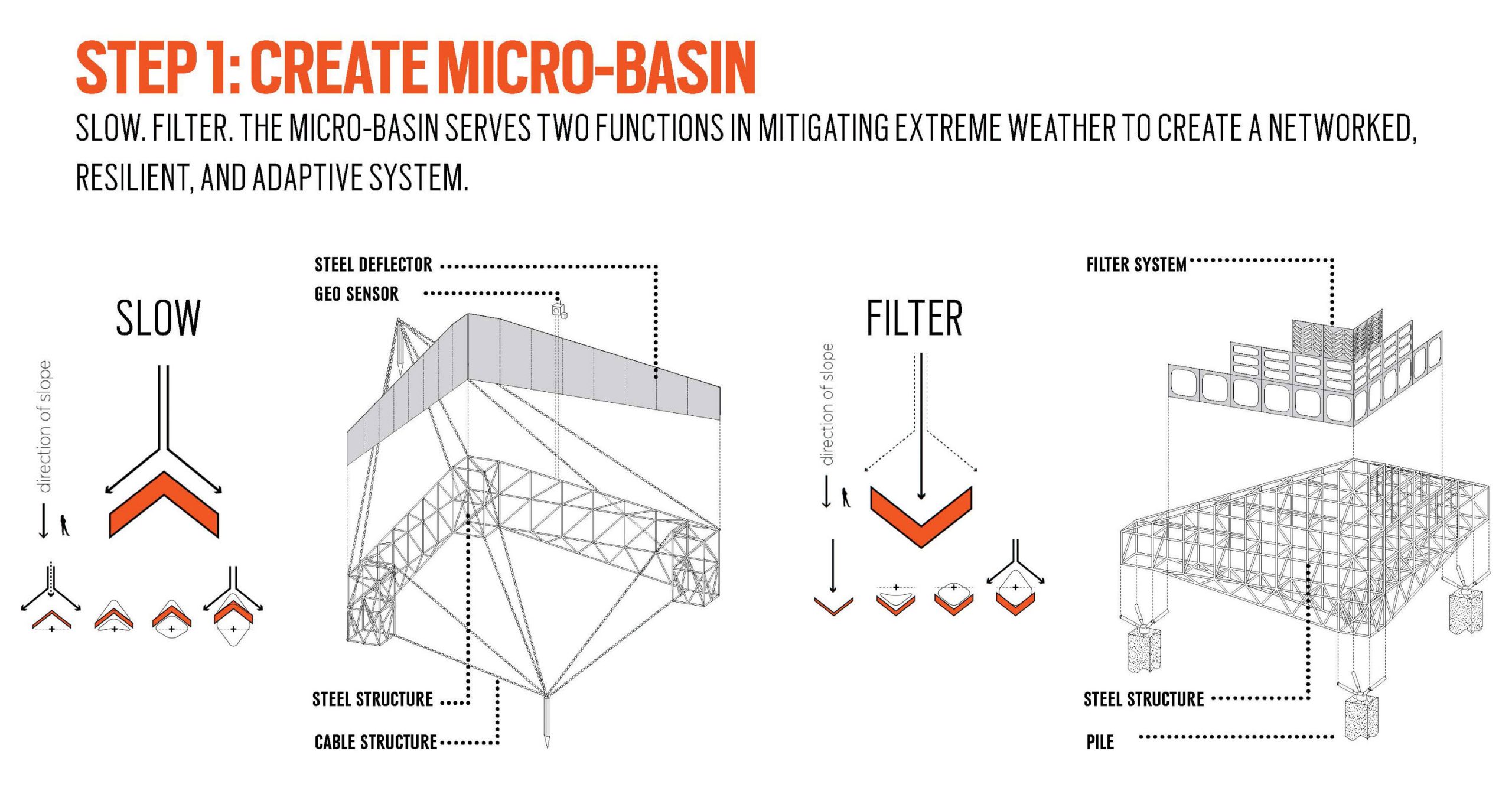

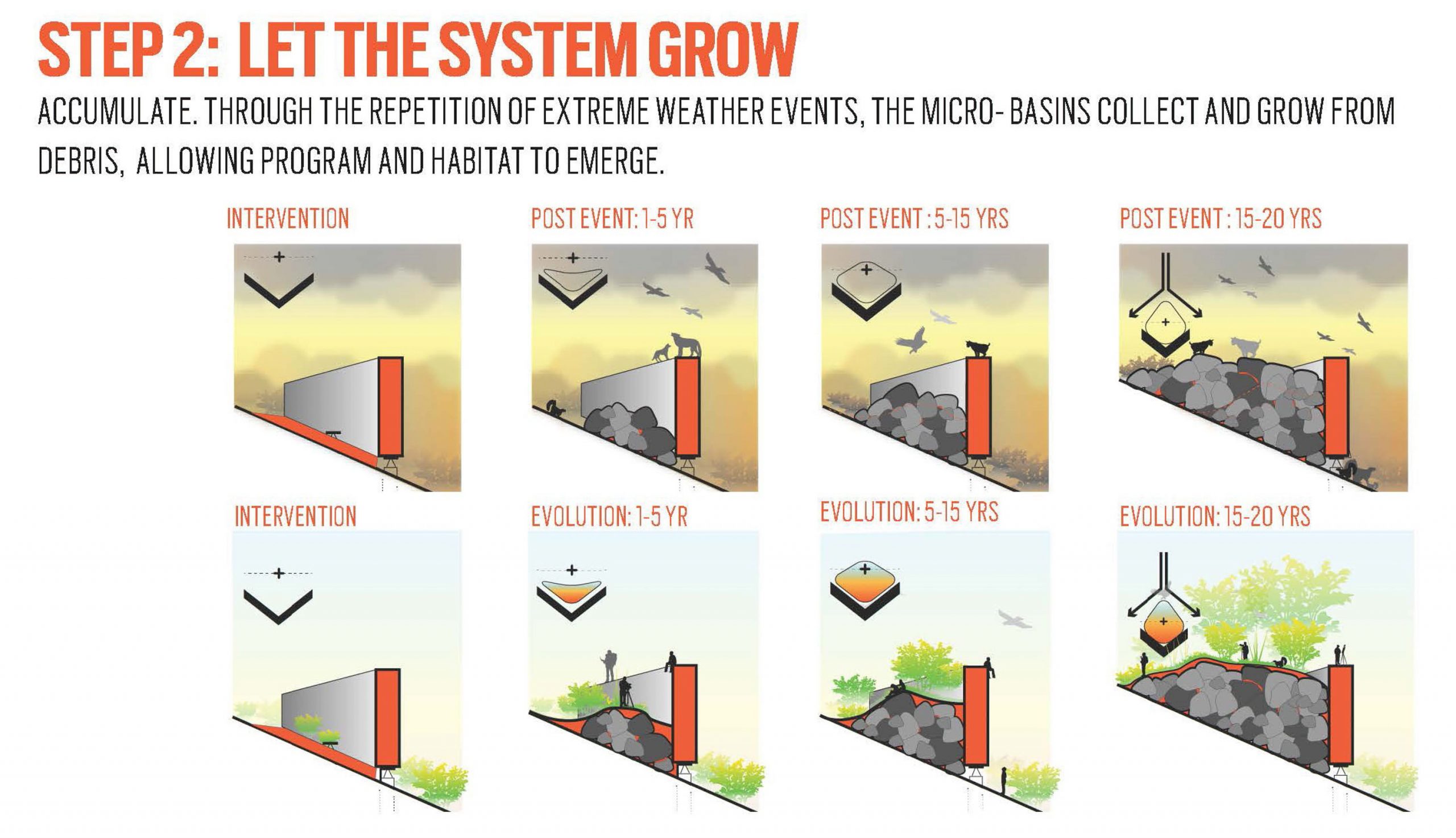

In contrast to the fixed and static infrastructure that currently attempts to control mega storms, this proposed landscape-based approach takes advantage of cyclical debris flows to create an ever more resilient system.

The new system begins with the siting of micro-basins; a simple gabion intervention. The micro basins serve two critical functions. When the micro basin’s point upslope they slow and divert debris, reducing the overall impact of the debris flow on urbanized areas. When faced downslope, the micro basins both filter and collect debris, creating a more aqueous flow.

Currently, following a mudslide, trucks clean out debris basins and then haul away the debris to landfills, at a rate of half a million cubic yards per year. This expensive solution carries a huge carbon footprint, and is also spatially unsustainable: the 1,365-acre La Puente Landfill, where so much of this debris has been trucked over the years, is now full.

However, by using a system comprised of re-used hillside materials, primarily rock and mud, the micro basins become opposite of the desolate concrete-capped catch basins that currently dot the edges of hillside communities; they become moments of thriving biodiversity and habitat.

After 15-20 years of extreme weather, this intervention would result in a network of micro-basins along the foothills, linking the canyons together in a single, dynamic system for extreme weather mitigation. As such, this process creates a closed loop system capable of supporting, and generating, multiple forms of urbanism within close proximity to disaster zones in the wilderness.

During periods of clement weather, this new infrastructure of mud, rock and steel would become the armature for new recreational and habitat opportunities, turning devastation into an asset for the local foothill communities. This new geology of mountain-making acts as a hybrid infrastructure of both natural and synthetic interactions aimed at re-thinking extreme weather and the space it creates.

This investigation fundamentally re-thinks the relationship between the city and the edge of nature from one of danger and contention to one of symbiosis and opportunity. By challenging the nature of mudslide infrastructure, this project also challenges the role of the landscape architect/ designer to move beyond the purely aesthetic and engage with the systems and processes that support urban and natural life.