By Tyler Collins

In the beginning, there was the bungalow. In the early decades of the 1900s this building type made its name synonymous with L.A. living to eventually become the California Bungalow, an affordable, attractive dwelling with cellular interiors rooms connected to porches and patios. Starting in the 1940s, Case Study Homes came onto the scene as a solution to provide low-cost homes in post-war Los Angeles. The typology gave agency to emerging architects, and ultimately became the modern dream home, which broke open the plan and connected the indoors and outdoors. From iconic Pierre Koenig homes to the more pervasive Joseph Eichler homes, the concept evolved into a typology that is now the ideal L.A. home. Today’s ideal home removes the walls completely and flows seamlessly into the outdoor where the interior is connected to landscape, water, and view in a holistic solution.

Here we explore the evolution of the L.A. home in a visual essay that maps the progression of housing in the city.

"A Bigger Splash," David Hockney, 1967

This painting captures typical expectations of residential life in LA including private outdoor space adjacent to conditioned interiors. Typically this fantasy was limited to the unit of the individual family and noticeably absent in the painting is any sense of community.

“No Splash” After David Hockney’s “A Bigger Splash,” 1967, by Ramiro Gomez, 2013

This painting revisits the utopian aspects Hockney’s earlier work to reflect on the maintenance of midcentury notions of the “good life.”

The Avalon, Sears, Roebuck, and Co. Modern Homes Catalog. 1921-6

Revisiting 20th century kit homes such as the Avalon, from Sears and Roebuck, documents early notions of the California bungalow and life on the West Coast. Consisting of “Six Rooms and Bath”, the bungalow’s cellular plan extend the living space through incorporation of a front porch.

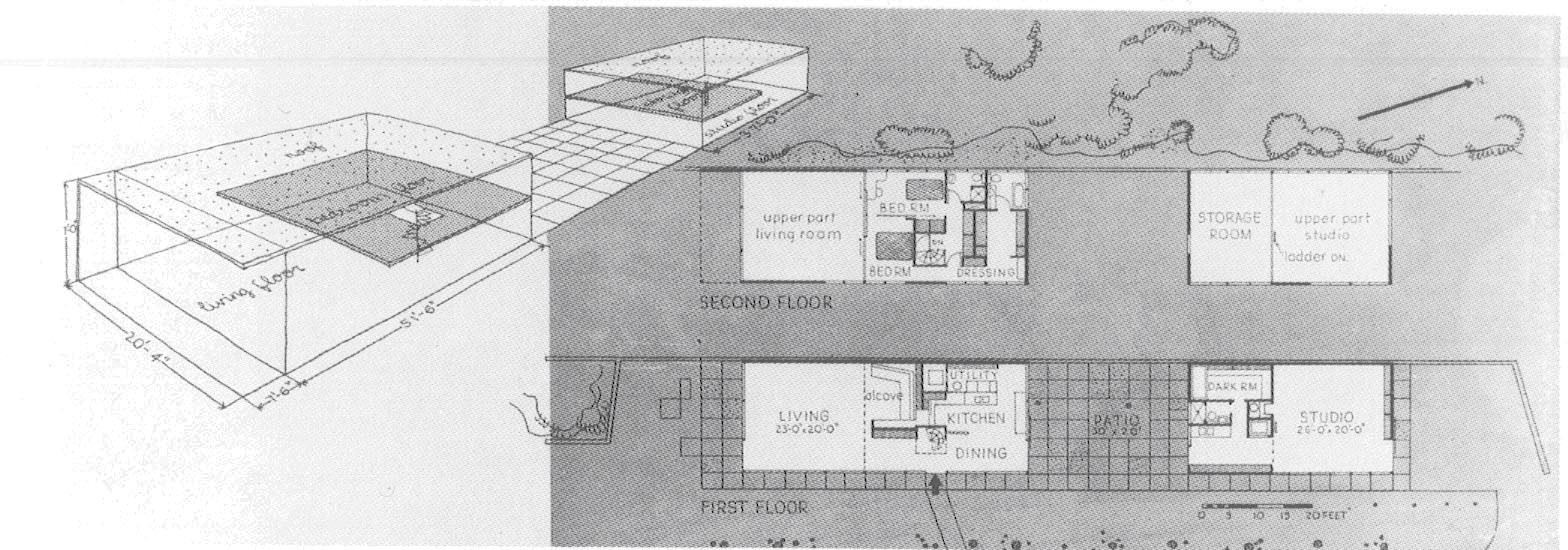

Eames House, Case Study House No. 8

Immediately recognizable for its association with the Case Study House program, the Eames House incorporated industrial means to produce a new classic. The Eames House incorporated new amenities such as a dark room and studio while introducing a patio to separate the wings.

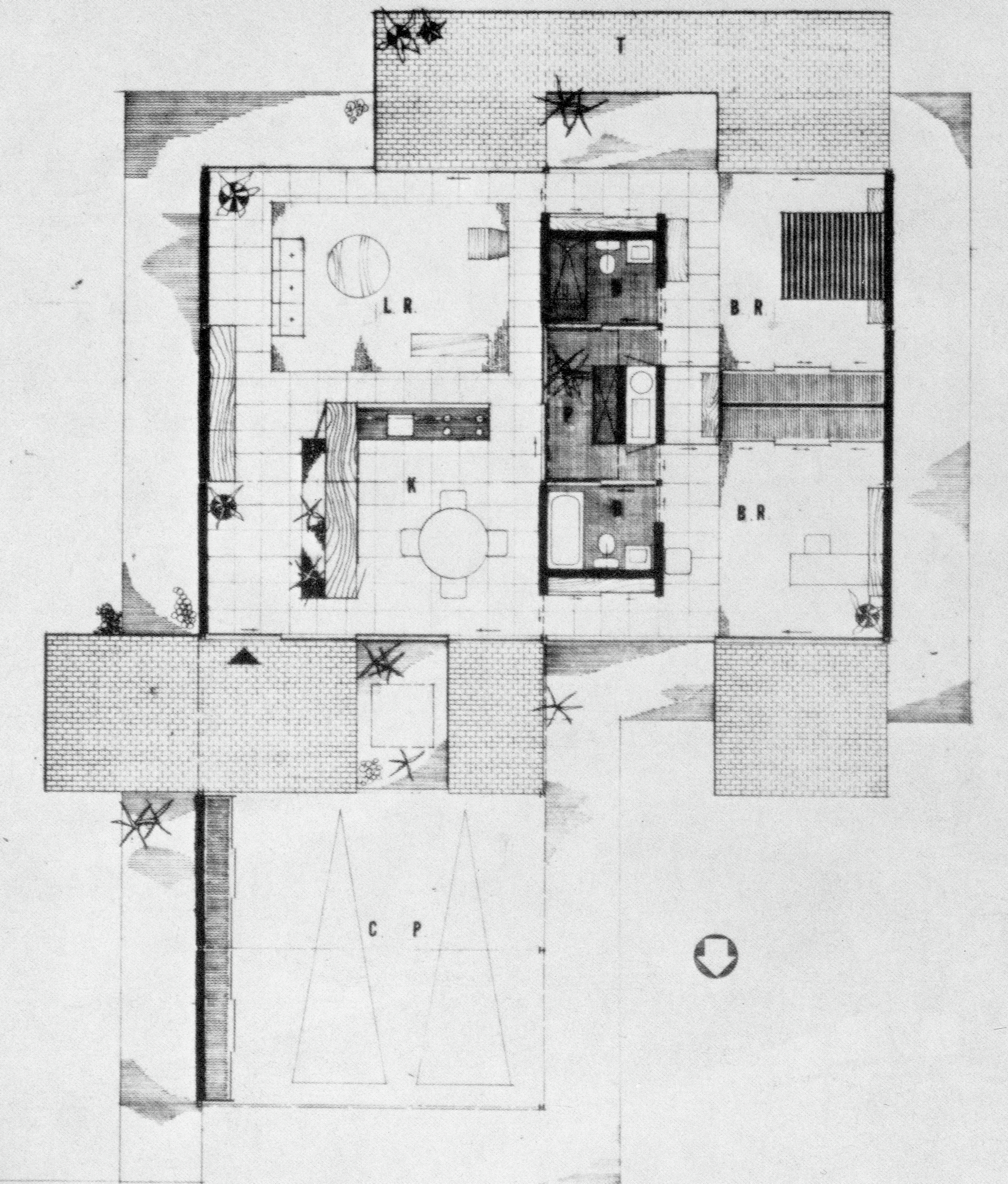

Bailey House Plan, Case Study House No. 1, Pierre Koenig. 1958

The Bailey House continues the Case Study tradition of incorporating exterior space as an extension of the interior. Through the strategic use of expansive glazing and a small outdoor court the threshold between interior and exterior remains permeable.

Hollywood Hills Living Room, Joe Sola. 2015

This photograph by Joe Sola from “A Painted Horse” presents the viewer with an essential aspect of the midcentury legacy as Riba, the painted horse, stands at the threshold between interior and exterior space. Indicating the seeming lack of boundary, the photograph reiterates early case study strategies by presenting the boundary as nonexistent.

Sheats Goldstein Residence, John Lautner. 1961-3

Much like the prior photo, this image of the Sheats Goldstein Residence captures the California dream at its most bare by presenting an architecture consisting solely of roof and landscape. Abandoning the traditional diagram of the house as four walls and a roof, Lautner’s iconic design orients living spaces to a view of the LA basin and creates interior spaces that bleed directly into the landscape.

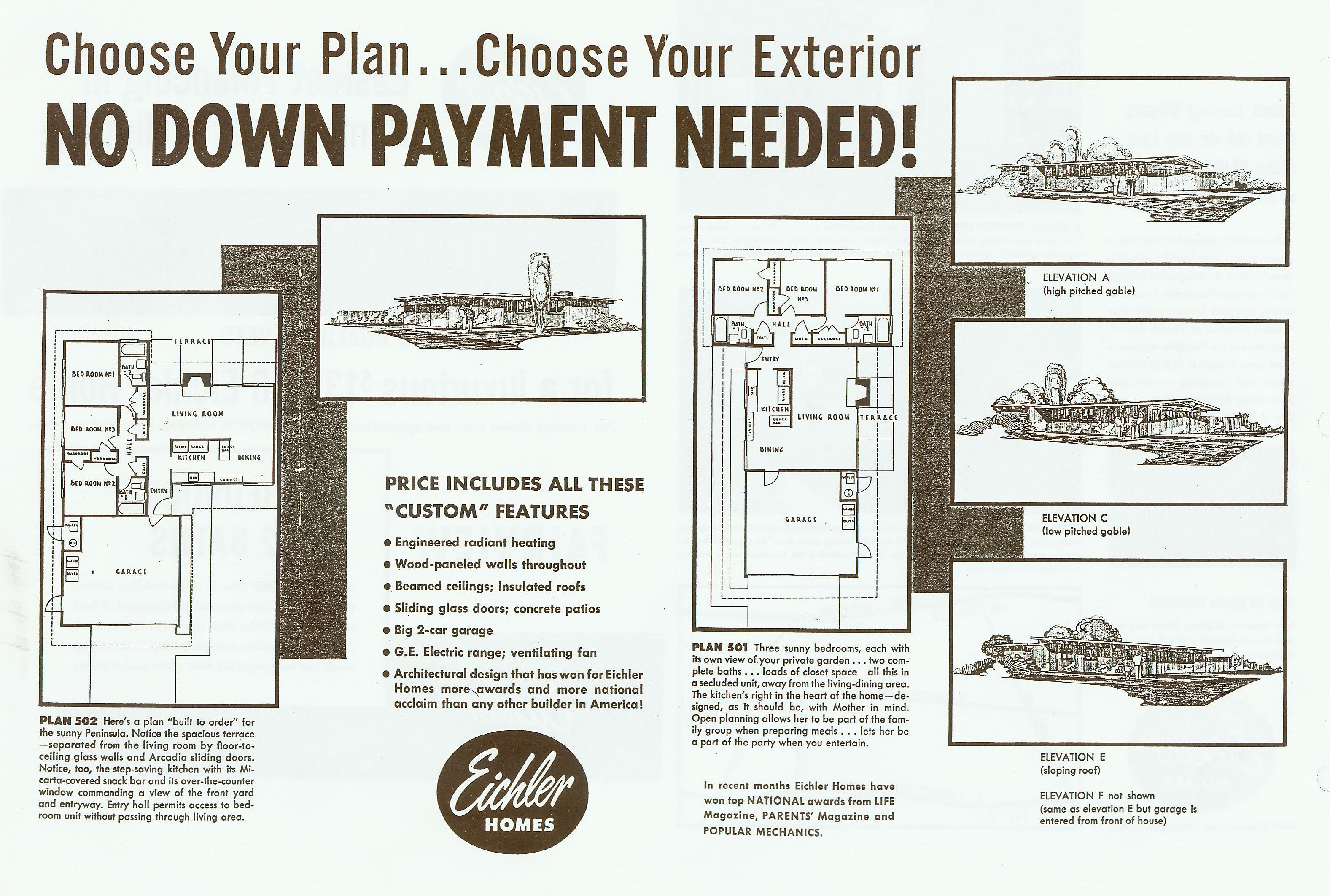

Eichler Home Advertisements

The progressive tendencies of the Case Study House program became typical of every day architecture in California. These advertisements for Eichler Homes incorporate strategies from the Case Study Houses while expanding their market reach to the masses.

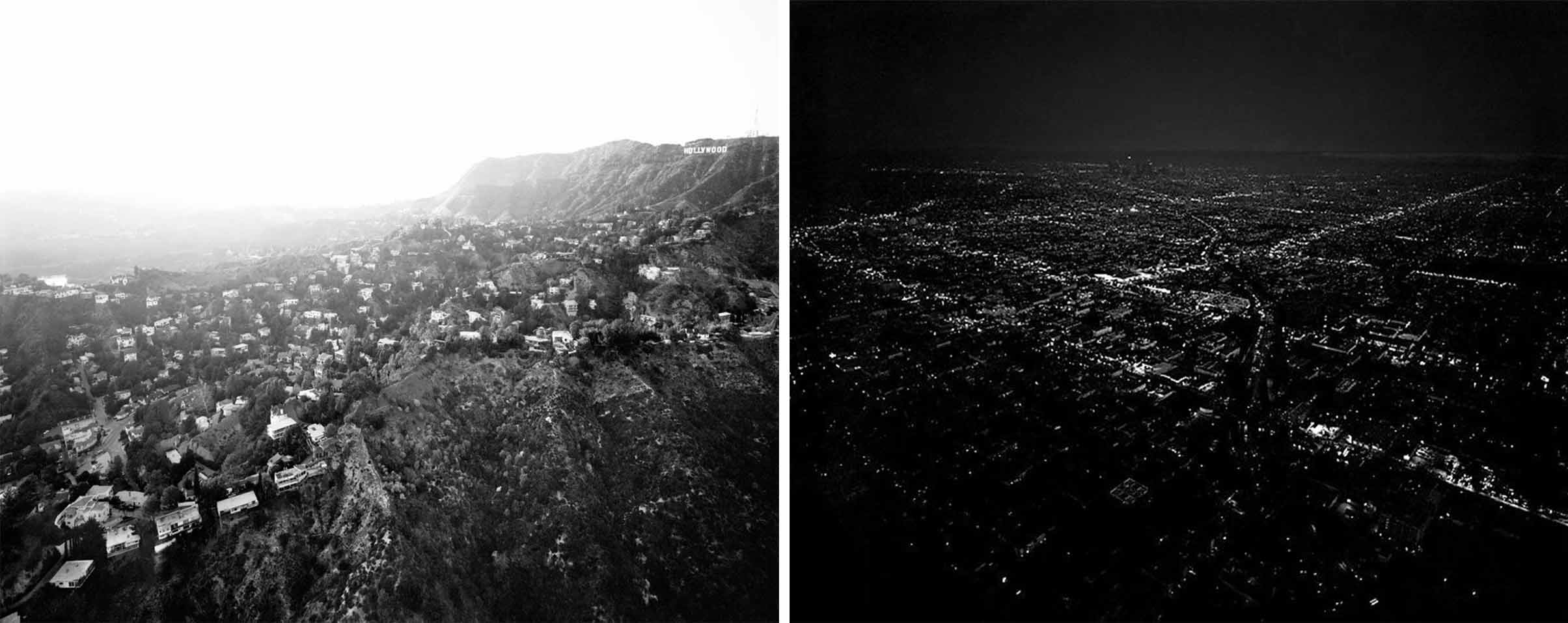

Left: “Hollywood Hills From Griffith Park, Beachwood Drive and Hollywood Reservoir at Left, CA. Michael Light”. 2004.

Right: “Untitled/Downtown Dusk”, Michael Light. 2005.

The prior images of Midcentury California architecture present a lifestyle of guarded leisure and seclusion. Most Americans associate the “good life” of the 50s with an image of the single family home that is reminiscent of Hockney’s painting, or really any of the Case Study Houses. Yet how does this fantasy scale and what limitations does it hit when accommodating an urban populace? Is it a fantasy that can address the commons?

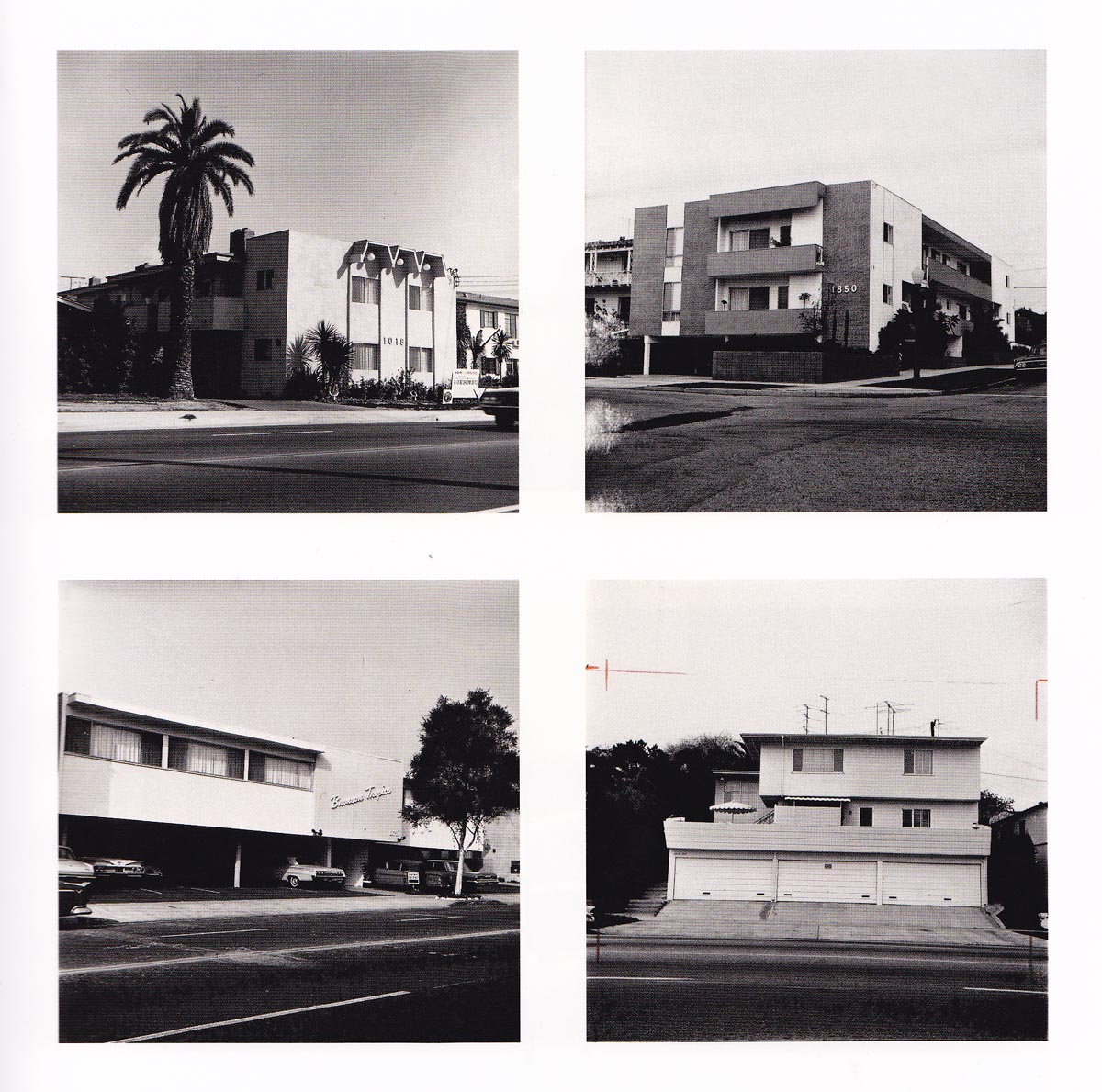

Some Los Angeles Apartments, Ed Ruscha. 1965.

This concern for the urban and its role in structuring the “good life” reoccurs in the work of Ed Ruscha. Through projects like his study of Los Angeles apartments we begin to see typical multi-family adaptations of California living that include typologies like the dingbat. Incorporating amenities such as covered parking and shared outdoor space, at times private patios, these photographs address the balancing act of an urbanized California.

Untitled, Dingbat Series. Judy Fiskin. 1982-3; Untitled, Dingbat Series. Judy Fiskin. 1982-3

Similar to Ruscha’s project, these photographs by Fiskin examine the typology of the dingbat as an essential element of California urbanism. Incorporating a decorative flourish above covered parking, the dingbat is ubiquitous throughout Los Angeles.door space, at times private patios, these photographs address the balancing act of an urbanized California.

Dunsmuir Apartments. Gregory Ain. Juliush Schulman. 1982-3.

Ain’s Dunsmuir Apartments developed early Case Study strategies such as expansive glazing and a continuity between landscape and interior living spaces. The architecture creates a shared landscape between adjacent units to link living spaces with the outdoors.

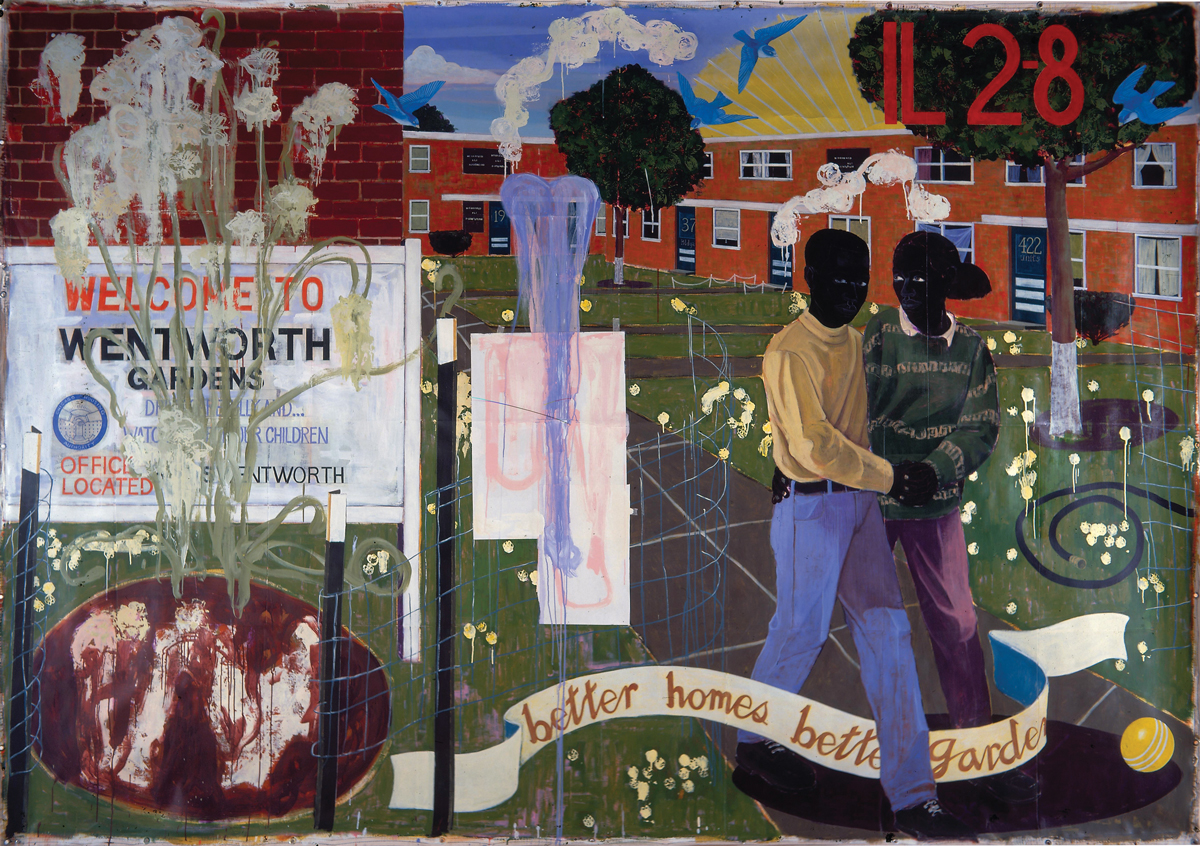

Better Homes, Better Gardens. Kerry James Marshall. 1994.

Marshall’s portrayals of life in Los Angeles social housing projects address the failures and successes of California’s urbanization. The scene includes a vast central landscape surrounded by a heavy brick boundary with two tenants strolling. The painting presents another idea of California living and interrogates the inaccessibility of the “good life” beyond the scale of the individual family.

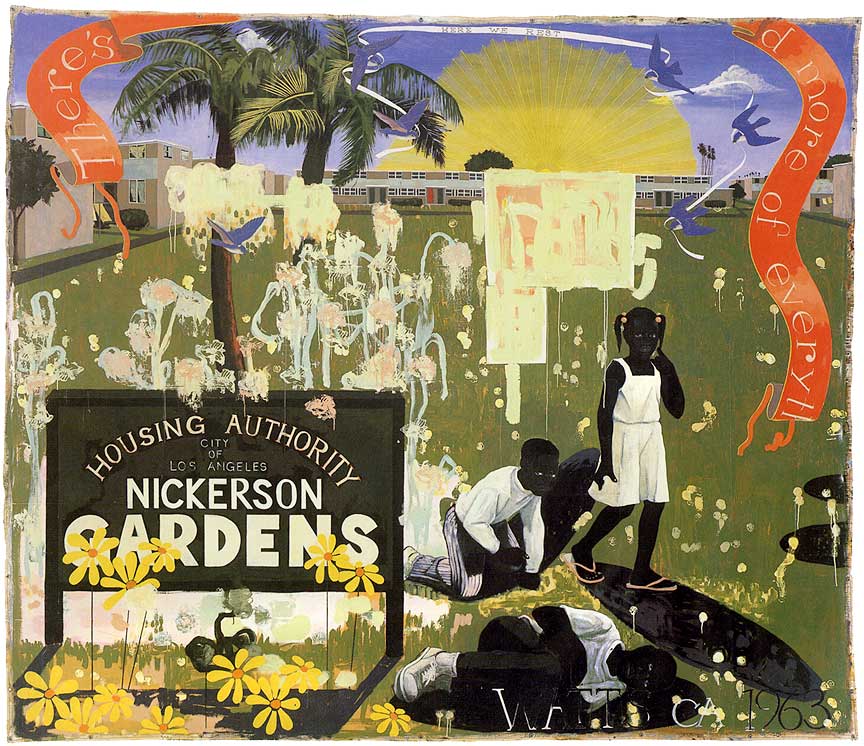

Watts 1963. Kerry James Marshall. 1995.

Another of Marshall’s social housing scenes depicts a similar central landscape surrounded by low buildings. Three figures inhabit the landscape while the surface of the painting exhibits scratches and flowers reminiscent of graffiti and decay.

Kenmore Small Lot Development by RIOS

Of late, RIOS has designed a series of projects that adapt midcentury strategies to craft unique domestic spaces emblematic of California living. Incorporating full height glazing, interior courts, and shared outdoor spaces enhance the experience of dwelling while balancing multiple scales of building. These projects are one way to carry on the legacy of defining new housing prototypes through the evolution of Southern California architecture.